Takayuki Nakamura Interview: From Moonwalker to Sky Soldier

An alumnus of SEGA, Takayuki Nakamura is one of the most successful independent video game sound creators. His portfolio includes the scores for diverse fighting games (e.g. Virtua Fighter, Kengo), puzzle games (e.g. Lumines, Peggle), and racing games (e.g. OutRunners, F1), as well as independent albums and sound tools.

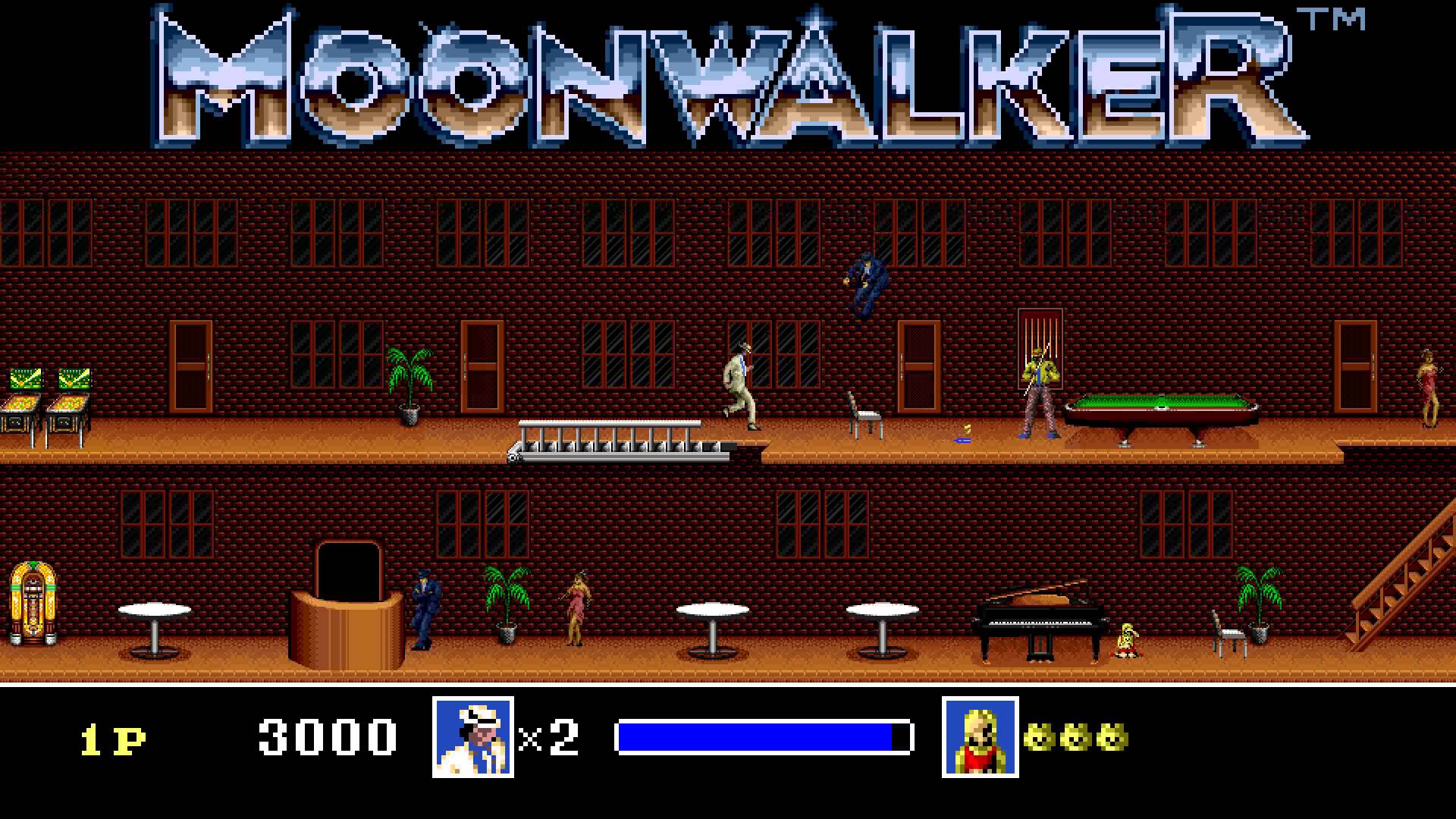

In this rich interview, coordinated with the kind help of Jayson Napolitano, Nakamura talks us through highlights of his career. His takes us all the way from his first work (Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker) to his latest project (Yuji Naka’s Rodea the Sky Soldier), with a special emphasis on fighting games. Along the way, he reflects on the inspirations for his ‘impulsive’ musicality and his struggles with Genesis and Arcade hardware.

Interview Credits

Interview Subject: Takayuki Nakamura

Interviewer: Chris Greening

Translation & Localisation: Stephen Meyerink, Elizabeth Bushouse

Editor: Chris Greening, Jayson Napolitano

Coordination: Jayson Napolitano

Interview Content

Chris: Takayuki Nakamura, thank you so much for doing this interview. First of all, could you tell us about your musical background, education, and influences?

Takayuki Nakamura: I’ve enjoyed music ever since I was a child. I was raised in a home that listened to a lot of music. My earliest memory is of using my family’s record player to listen to all the hit songs of the day and such. I think that was even before I started going to elementary school.

I think one of the first things that really got me started was in my fifth year of elementary school when my father bought a component stereo. From that point on, I would record songs from the FM radio or records I had borrowed and make my own original mix tapes.

When I became a middle school student back in 1980, I started playing the guitar. Back then, my favorites were artists like Toto and Van Halen. I also started a band with my friends from school, but we pretty much exclusively covered Japanese “new music” [translator’s note: a term used to describe popular music in the 1970s and 1980s in Japan]. When I started high school, I came across jazz, and the first things I listened to were by Keith Jarrett and Sadao Watanabe.

Chris: What led you to becoming a video game sound creator?

Takayuki Nakamura: When I became a college student, some friends and I started a T-SQUARE cover band. My college was a business school, so I didn’t get any specialized music education. Even so, I had a vague dream that I wanted to advance the world of music.

When I became aware that game companies were recruiting composers, I resolved to apply, even though I didn’t fully understand the work. However, in the 1990s house and techno were in vogue, and we were headed full speed towards the age of electronic music. I had absolutely no experience making music with a computer, but thanks to my strong interest in the field, I think I was able to make it my thing pretty quickly.

Chris: What were your first works at SEGA?

Takayuki Nakamura: A little before I was taken on full-time, I worked for SEGA Corporation part-time in the summer of 1989 on Moonwalker [editor’s note: a Genesis platformer featuring Michael Jackson]. I remember working with Michael Jackson’s “Bad” so it could be played on a Genesis. I listened to it, copied by ear, and then converted it into MML data [translator’s note: music macro language]. The boss battle song was the first one I made on the job. I didn’t know the field at all, so I was trying to learn on the job at first.

I worked on ESWAT: City Under Siege at the exact same time as I did Moonwalker. I don’t think there was much of a schedule, but I do have a recollection of working on it with a senior co-worker [editor’s note: You Takada]. Like with Moonwalker, I recall being taught how things worked while I was actually doing them.

My first game on an arcade chipset was Columns II, which I worked on under the same senior composer. As before, I remember starting out on the work with the help of a senior, but my memory’s a little fuzzy on things like what songs I worked on personally and such.

Chris: You got to work on Outrunners too if I’m not mistaken?

Takayuki Nakamura: Yes. I was incredibly excited to be put in charge of this one, since it was the sequel to a really popular game. We were able to use entirely sampled sound sources and work with MIDI programs that I had developed myself. It was a game in which the technical aspects of the sound design underwent a big change.

Chris: Your music is incredibly diverse: you’ve delved into electronic, jazz, rock, orchestral, and traditional Japanese music among others. How have you developed such versatility? Were you always versatile or have you developed this trait on the job?

Takayuki Nakamura: To begin with, I absolutely love music. There aren’t really any limits to the music I like. The kind of music I like is the kind of music that moves me, that makes me feel something — music that sends a jolt to my senses.

In that same way, when I begin work, I chat with the director a lot to figure out what kind of sound the music needs to have. Through that, we can create an image of where we want the soundtrack to go. From my point of view, rather than saying “I’m purposely making music in many genres,” I think the diversity of my music is more the result of trying to create something that captures the sound I’m looking for in a particular project.

Chris: While you’ve worked on racing and platform titles, you’re best known for your works on fighting and puzzle games. What has made you a go-to composer for such games? What principles do you think are most important when scoring such titles compared to your other works?

Takayuki Nakamura: As for why I started working on fighting games, I think that’s strongly linked to the changing game market. When I started at SEGA, racing games were overwhelmingly popular. Back then, a lot of them were being made, like Outrunners and F1 Exhaust Note, but with the release of Street Fighter II, fighting games became popular. I think I responded to that demand with Virtua Fighter.

Beyond that, the popularization of portable gaming lead to the development of many games that could be easily played, like Lumines—that was a game whose goal was to immerse the player through music. For me, those were important titles. I’d like to try and make more soundtracks for both fighting and puzzle games in the future.

Chris: While you’ve talked principally about your works on puzzle games in the past, such as Lumines, we haven’t heard you talk much about your fighting scores. Your breakout work was Virtua Fighter as you say. How did you rise the challenging of scoring SEGA’s answer to Street Fighter II. How did you capture the tone of this game and its featured characters?

Takayuki Nakamura: When I was composing for Virtua Fighter, there was certainly pressure to surpass Street Fighter II. However, in terms of sound, I didn’t particularly refer to it. Rather than that, the number one thing I concerned myself with was how to transmit sounds to player through generic arcade cabinets. That was very difficult to do. To that end, I worked on things like improving the speakers and equalizing the sound mix, mainly.

Chris: After leaving SEGA, you went on score two fighting games published by Square: Tobal 2 and EHRGEIZ. What inspired your contemporary approaches for these titles? Was the PlayStation console less restrictive than the arcade soundboards you previously worked on?

Takayuki Nakamura: Right before I stopped working at SEGA, I had become the manager of their sound department, so the circumstances were quickly becoming unconducive to actually composing. Because of that, even though I only worked for Square for a brief period of time, I was able to create music in an overwhelmingly good environment.

Tobal 2 was the first game I worked on after leaving SEGA, so I absolutely wanted to make it a success. Using an approach that drew on all the fighting game music I had produced so far, I think I was able to compose a variety of different songs. With EHRGEIZ, I put emphasis on the more impulsive parts, challenging myself to change my musical style in a big way.

For both games, I handled the sound programming alongside composing the music, which was pretty commonplace up to that point. Because of that though, there were also painful times when I couldn’t get things to sound the way that they did in my head. Even so, after that, that new impulsive style went on to become my usual sound.

Chris: Since then, you’ve worked on numerous fighting games set in traditional Japan, most notably the Kengo titles. How did you create a period setting for these titles? What inspired you to take a more subdued approach for these titles compared to your other works?

Takayuki Nakamura: I was independent at the time, but the first ones to reach out to me were the Kengo team. The company that developed these games [editor’s note: Genki], was formed by some former co-workers from my time at SEGA. They knew I had made a lot of music for fighting games and so commissioned me.

Kengo might not be a game people outside Japan are familiar with, but it’s really fun. Even though I used traditional Japanese instruments when writing the music, I tried to make it in such a way that it didn’t sound like traditional Japanese music.

Chris: Talking of reuniting with SEGA employees, you worked on your latest work Rodea the Sky Soldier with fellow SEGA veteran Yuji Naka. Given you were in different teams at SEGA, had you ever met before? What drew you to each other on this project and how did you work together?

Takayuki Nakamura: The first time I met Naka-san was when he was working on Ghouls ‘n Ghosts at SEGA. I was new to the company at the time, and I remember him giving me a tour around the development room. After he had been transferred to SEGA of America, I went on a business trip to America and we met in Los Angeles. But when I talked to him about that, he didn’t seem to remember! Back then, he was a top-tier developer, so I think he probably met with a lot of employees.

Chris: The title features one of your most eclectic soundtracks to date. Could you tell us more about your inspirations for this title? How does the music work both in the game and as a stand-alone soundtrack?

Takayuki Nakamura: Actually, Naka-san might have been envisioning a more orchestral kind of sound. When I played around with a prototype of the game, I got a strong, exhilarating feeling of dashing about in the sky, so an acoustic guitar accompaniment came floating into my mind quite naturally.

Even though it’s an action game, it also has a romantic sort of story in which robots develop human hearts, so I decided to divide my composition style based on whether the music was for cutscenes or for gameplay.

Chris: Many thanks for your time today. What can fans of your music look forward to in the future? Do you have any messages to readers around the world?

Takayuki Nakamura: If your interest in Rodea‘s music happens to lead to you becoming interested in me as well as the rest of my works, that would make me extremely happy. I’ll probably end up being involved with a lot of titles in 2016. I’m going to continue to work hard so that my music can reach everyone, so thank you very much for all of your support!

Takayuki Nakamura’s work is available to Western audiences through iTunes, including his latest soundtrack Rodea the Sky Soldier Original Soundtrack, the seasonal Lumines Remixes Winter, and his solo album.

Posted on December 26, 2015 by Chris Greening. Last modified on December 30, 2015.

Correction: Moonwalker wasn’t his debut title, instead it was ESWAT: City Under Siege.

No, read the interview in full. He clearly states, while he worked on Moonwalker and ESWAT at the same time, the boss theme for Moonwalker was the first ever track he ever created for SEGA. ESWAT was released a month earlier than Moonwalker, but Moonwalker was still his first game work.

Sorry for my ignorance. I forgot the interview mentioned that, so I went by release dates.

Anyway, nice work! It was an interesting interview.

No problem! I thought the same as you till this interview. Glad you liked it!