Final Fantasy VI Symphonic Poem Listener’s Guide

Overview

With the release of the recent chart-topping Final Symphony on many digital retailers’ classical charts, it seems that the discussion of the connection between video game music and classical music is as relevant as ever. The album release not only employs the famed London Symphony Orchestra, but also features three large-scale works for the orchestra: a symphonic poem, a piano concerto, and a full 40-minute symphony all based on the scores of Final Fantasy VI, VII, and X respectively. Like any classical work, these pieces are not meant to be just enjoyed in passing or as background music. Rather, they are meant to be standalone, engaging experiences that becoming more rewarding with each listen as the listener uncovers more and more of what lies in the works.

With this, I invite listeners to journey further with me into the wonderful pieces that Spielemusikkonzerte have crafted on Final Symphony. I don’t claim to have found all of the secrets and wonders embedded in these pieces, and nor would I document them all here even if I had. There’s something to be said about finding them on one’s own. What I’ll provide here is a starting point that listeners can work off to hopefully deepen their understanding and appreciation of this crucial stepping stone in video game music history.

This first article will focus on Roger Wanamo’s “Final Fantasy VI Symphonic Poem: Born With the Gift of Magic”, while the piano concerto and symphony will follow in subsequent articles. Roger himself has given a quick recap on the structure of the work on the official website and in an interview with SoundtrackCentral, but here I will expand on it with further resources and detail. If you haven’t yet picked up the album but want to learn more, feel free to follow along with the album on streaming services such as Spotify and YouTube. Alternatively, there is also the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra performance available online, though any references I make to times in this article are to the album’s London Symphonic Orchestra recording.

The Symphonic Poem

In the first major work of Final Symphony, Roger Wanamo arranges key themes from Nobuo Uematsu’s score of Final Fantasy VI and tells a narrative through the framing of a symphonic poem. This style of musical storytelling is very accessible, being free with no structural or compositional form requirements. Unlike symphonies or concertos which have clear and distinct movements with breaks in between, a symphonic poem tends to be a single-movement work, although it can have distinct sections and atmospheres as it tells the different parts of its story. Musical themes and motifs are assigned to characters, events, or other significations, and so the music themes acts as words and their interactions make the story. The symphonic poem idea is a fairly recent in its conception, and is the most evident example of a story told through music.

The Story

Final Fantasy VI features many characters and story elements, but Wanamo’s work chooses to focus on just two characters: the central protagonist and heroine Terra (aka Tina in Japan), and the antagonist Kefka. The title “Born with the Gift of Magic” refers to Terra, who is introduced as a puppet of the Empire, under the dictatorship of Emperor Geshtal. She manages to escape, but at the cost of her own memories. The poem then briefly shifts its attention to Kefka, who is a psychopathic general of the Empire. Dressed as a jester, he is seen to fall further and further into madness. The poem then returns to Terra who discovers the hidden world of magic users as well as her own magical abilities. With this new-found power she enters into battle with Kefka, who has overthrown the Empire and seeks to take over the world. The battle escalates and comes to a climax that cuts abruptly, with a few moments of quiet before Terra emerges victorious.

The Themes

The score for Final Fantasy VI includes over three hours of content, assigning themes and leitmotifs to the many different characters, locations, and events throughout the game. The following are the themes that are used in the symphonic poem, with information about their original appearance within the games. The alternate names listed are translations of the Japanese names. This article will refer to the pieces by their proper English names. I’ve provided samples of the recurring leitmotifs to help with identification.

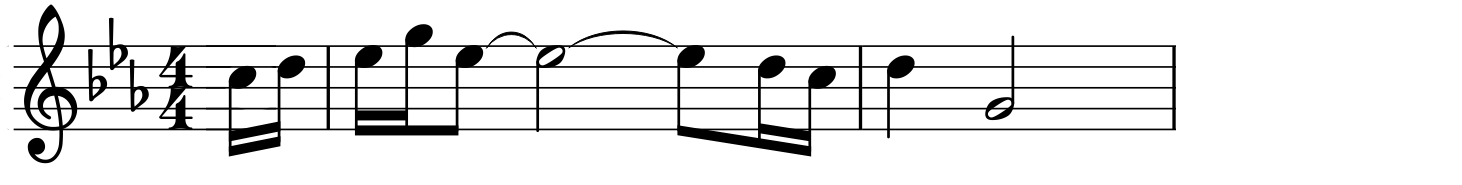

“Terra” (aka “Tina’s Theme”) is the theme for the protagonist Terra. The following fragment is used principally as her leitmotif, although more of the theme also appears in the poem. Terra’s leitmotif also has many incarnations throughout the original score.

Audio Player

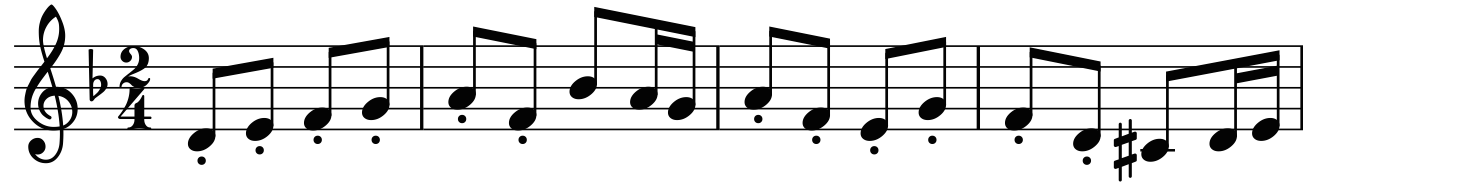

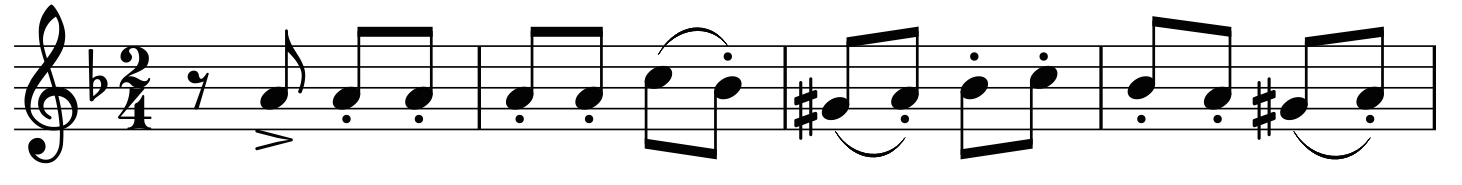

“Kefka” (aka “The Sorcerer Kefka”) is the theme for the antagonist Kefka. His theme can be broken into various figures, two of which are used as leitmotifs throughout.

Audio Player

Audio Player

The first of the location and event themes is “The Geshtal Empire” (aka “The Ghastra Empire”), representing the oppressive Empire which is in power at the beginning of the story. Similarly, “Another World of Beasts” (aka “Esper World”) signifies the discovery of of the hidden realm where the magic users reside. There are also shorter appearances of “Overture” from the opera scene found in the game, as well as motifs from “Omen” (aka “Opening Theme”) which is the brooding opening song of the game, known for its bell chord opening as well as a six-chord figure that signals the coming of an evil many times throughout the game.

Several battle themes from the game are used in the climactic battle of the poem, though they do not necessarily signify their original contexts. “The Unforgiven” originally plays during the Doma siege, while “Save Them!” (aka “Protect The Espers!”) plays during the battle over the frozen Esper, both of which are not signified here in the poem. “Metamorphosis” plays a number of times throughout the game, including during the scene where Kefka is wreaking havoc on the world and when Terra loses control of her powers. “Battle” is the regular battle theme in the game, playing for regular enemy encounters. “Dancing Mad” plays during the final confrontation with Kefka in the game, and features many variations and elaborations on “Omen” and “Kefka”. However, only part of the final variation is included in the poem.

The Work

The opening of the symphonic poem starts with the overture to the opera scene, which originally occurs partway through the game. Its inclusion is more for rousing introduction than something with narrative significance in the context of the symphonic poem. Within this opening, Wanamo fits in flashes of the leitmotifs for Terra and Kefka, priming listeners to encounter these characters.

A lone trumpet (0:58) signals that start of the narrative with the entrance of the Empire, opening to the bleak introduction of the game’s story. “The Geshtal Empire” plays predominantly while Terra’s motif plays underneath it, the latter being forced into the harmonic progression of the Empire theme, relfecting her status as a pawn under the Empire. Eventually Terra’s theme does manage to break free, but the inversion of the melody in its second part suggests that all is not yet well with her. The Empire theme returns and fades away, this time without Terra’s motif.

An ominous bell chord sets the stage for the introduction to Kefka. His theme (3:40) is played simply and playfully at first, capturing his jester-inspired appearance. Although he too works under Emperor Geshtal, his theme is not subject to the Empire theme as Terra’s was, since Kefka is autonomous with hidden motives of his own. With each repetition of Kefka’s theme the music becomes more grandiose and chaotic, reflecting Kefka’s descent into madness. Contributing to this is Wanamo’s tinkering with the key and meter of the theme, disorienting the listener at each turn. Kefka’s theme comes to a climax, then settles back down allowing the focus to shift back to Terra.

Terra finds the mysterious Esper World (7:21) where magic users (Espers) have taken refuge. Wanamo makes use of the celeste, which is likely a nod to John Williams’ association of the instrument with magic in the popular first Harry Potter scores. Included in this segment is Terra’s discovery that she too was born with the gift of magic, at which point her theme is also poignantly stated on the celeste (9:12). The events at the once-peaceful Esper world begin to escalate as Kefka’s theme resurfaces underneath, and the time comes for a showdown between Terra and Kefka.

The start of the battle (10:57) is signalled by “Metamorphosis”, which then quickly gives way to the 6-chord motif of “Omen” overtop of the bass line of “Battle” before launching into the quick and furious strings of “The Unforgiven”. The battle rages on in “Battle” (12:03) and “Save Them!” (13:03), with Terra’s and Kefka’s motifs making appearances. Just as the characters do in combat, the different themes and motifs begin to weave in and out of each other, often interrupting in attempts to come out on top. The confrontation is brutal and chaotic, and soon comes to a violent climax. The entire orchestra drops out, leaving the fate of the two characters momentarily a mystery (13:50).

Out of the silence, as the dust settles the lower strings fade in. At first things are barely discernible but eventually the notes resolve into the ending of “Dancing Mad”; Kefka is seen to have fallen. Terra’s motif emerges, and her theme is finally allowed to victoriously shine with an arrangement in line with the original score. It’s a militaristic arrangement that no longer has the oppressive overtones of the Empire, but rather is fully its own piece which marches onward to a bright future.

The overture theme that opened the symphonic poem returns (17:21) and closes the piece out.

Summary

That concludes our journey through Roger Wanamo’s retelling of the epic Final Fantasy VI story, told through powerful orchestrations and wonderful elaborations. His signature overlaying of musical themes makes for effective narrative techniques, and those with keener ears will enjoy further dissecting his work. It’s pretty incredible to know that as great of a representation of Final Fantasy VI as this was, there is still a wealth of material from the original score and story that Wanamo did not include. I’ll certainly be on board if he ever decides to revisit this magical universe.

Side Notes

-Terra’s theme is never actually played in full during the poem. The poem chooses to focus on the first half, omitting the second half of her theme. Most of other themes however are fully displayed, including Kefka’s.

-Although the opera overture bookends the symphonic poem in E♭ major, the home key of the narrative is its relative minor, which is the C minor of the opening to “The Geshtal Empire” and of the closing rendition of “Terra’s Theme”. This is accentuated by the gorgeous v-V-i structure formed at the end of the poem by the Kefka’s death in G minor, the raised leading tone in the blossoming of Terra’s motifs, then the final settling into C minor of Terra’s restated theme.

-The minor major 7th bell chord at 3:16 may remind listeners of the opening of “Omen” (which would be appropriate here), but the bell chord opening of “Omen” is actually comprised of successive perfect fourths.

-It may seem an odd choice to include “Battle” rather than the proper theme of the final battle with Kefka, “Dancing Mad”. However, “Battle” also rather obscurely (perhaps unintentionally) contains shades of Kefka’s themes in its figures. But I assume that Wanamo was simply looking for a more neutral battle theme to better accentuate Kefka’s interruptions.

-Wanamo manages to insert a number of imitations of Kefka’s infamous laugh throughout the poem, to great and creepy effect.

Also take a look at the write-ups on the other major pieces of Final Symphony, Masashi Hamauzu’s Final Fantasy X piano concerto (orchestrated by Wanamo!) and Jonne Valtonen’s Final Fantasy VII symphony! Also check out the official website to find out where you can purchase the album.

Posted on March 6, 2015 by Christopher Huynh. Last modified on August 24, 2023.

Excellent write-up, Christopher! I haven’t checked out Final Symphony myself yet, but definitely intend to. I’ve heard nothing but great things about it.

I’m personally very excited for the Final Fantasy VI sections. I’m a big fan of the original symphonic interpretation of the Opera which was originally on the Orchestral Game Music Concerts series, so it’s definitely going to be interesting to hear it once again with the London Symphony.

Thanks Oliver. You definitely won’t be disappointed! Except maybe about the Opera, which is really only in the opening and closing. But who knows, perhaps in a future concert it will be featured more prominently!

Well I got the album off of iTunes the other day and have been listening to it nonstop ever since. This is no doubt the best orchestral VGM album on the market now. I actually haven’t played any of the FF games apart from a little bit of the first, but am a very big fan of the music. I believe that anyone, VGM listener or not, FF fan or not, can definitely enjoy Final Symphony.

Yeah, I was somewhat disappointed that it didn’t include the entire Opera, but FFVI’s music is so great that it makes up for it. Still hoping for a full performance one day, though. Your writings on select tracks are very interesting! It’s amazing you can write so much on just a single piece of music. Guess that just shows how much intricate composition is involved.

Loved this analysis! I’m writing a Wikipedia article on the concert series, and I’m definitely citing this. Looking forward to the other parts!

Wow! It’s great that you’re taking that on, and I’m glad that this will help towards that. Thanks!

PresN, if you’re ever interested in using your knowledge to help GMO out too, let me know at chris@vgmonline.net Your contributions are excellent!