Daniel Lindholm Interview: A Westerner Scoring Japan’s Biggest Games

Daniel Lindholm has wrote music for several of Japan’s biggest franchises in the past few years, among them Resident Evil, Yakuza, Pro Evolution Soccer, Gran Turismo, and Lollipop Chainsaw. The Swedish-born composer has brought Western-influenced approaches to Japan on various large-scale collaborative scores.

In this interview, Lindholm discusses his background, philosophies, and approaches to writing music. He details his experiences on various major franchises, going into particular detail about his roles on zombie titles Resident Evil 6, Yakuza: Dead Souls, and Lollipop Chainsaw, before candidly giving his perspectives on Eastern versus Western game development. He supplements the interview with an exclusive collection of ten previously-unreleased demos and other music clips.

Interview Credits

Interview Subject: Daniel Lindholm

Interviewer: Chris Greening

Editor: Chris Greening

Coordination: Chris Greening

Interview Content

Chris: Daniel Lindholm, many thanks for talking to us today. First of all, could you tell us about what led you to become a composer? What is your musical background, influences, and education?

Daniel Lindholm: One of the reasons I wanted to become a composer was that I loved movie music since I was very young. I guess my main influences always reflect something from my past; what I like about those old movie scores is the tensions, the rhythms, and the flare that the music used to have. So basically I like to pay tribute to those classic movie score elements and bring them into the computer games.

I composed my first pieces when I was about nine, though I started to take piano lessons from my mom from the age of five. But it also helped to have two older brothers and a father who were all into music. So just like my brothers before me, I entered the music academy and started to master the saxophone as the main instrument, and later I went into music college to learn more about instruments and musical styles. The next logical step was to learn the music theory and I could only get that at the college. Of course, I tried my best to write music on “non-classical” platforms like “Noise Tracker”/ “Digi Composer” for the Atari ST and later went on to “Fast Tracker II” on the PC.

My main inspiration for my game scores comes mostly from film and bands like: Jerry Goldsmith, Arthur B. Rubinstein, Lalo Schifrin, Hans Zimmer, John Williams, Harry Gregson-Williams, Don Harper, Nick Glennie-Smith, Don Davis, Alan Silvestri, David Holmes, John Williams, Trevor Rabin, Meshuggah, Prodigy, Clawfinger, Nine Inch Nails, Toto, Mezzoforte, Morten Schantz, Nils Landgren & Funk Unit, Maceo Parker, The Crusaders, Jamiroquai, The Brand New Heavies, Extreme, Dream Theater, Symphony X, Stratovarious, Yngwiee Malmsten, Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Rob Hubbard, Kevin Riepl, Martin Galway, Yuzo Koshiro and many many more… the list is just a fraction and it just keeps on growing.

Chris: Though you originate from Sweden, you have spent your last eight years in Japan. What took you on this path? As a Westerner, how were you able to make your breakthrough as a composer in Japan?

Daniel Lindholm: It all started when I was around six years old and my parents had rented some animes from the local video store. My interest for Japan opened up right there with Starzingers (SF Saiyuki Sutajinga) and I had wanted to whisk myself away to Japan ever since. It was a tough decision to make, given it would mean leaving my parents (I’m the last out of three sons).

Before that, I had one outing away from my country for about six months in Taiwan; despite having no plans whatsoever, I managed to secure jobs really easily outside my home country in weeks. But when I got home to Sweden, it was impossible to find a job despite much looking. Luckily, I got the chance to stay at my parents home while I was job-hunting, but the harsh social/work conditions that the government pushed onto us were ridiculous. In two years, I only had one(!) interview. During this time, I was also just a “temp” at a music studio and could get a small “fee” for spending my time at the place. That gave me a chance to start saving that money for a ticket to Japan. On watching my friends play on their PS2 and Metal Gear Solid 2, it all fell into place. I realized my passion for movie music could be incorporated into games and my mind was set.

When I finally arrived in Japan in 2005, the next step was “Where should I go? Who should I talk to?” While trying to cover my bases financially, just by desperation or pure luck I wrote into a free “gaijin”-paper and put an ad basically saying: “Media-composer looking for work for Radio, TV, and Games”. Two weeks later I get a response from a media company and I went there with my laptop, showed them my stuff, and got a sponsorship for a VISA. But they said that they could not guarantee work all the time, so finding a side-job as a teacher would be one way to stay in a “safe-zone”. So I did that and found that there is lots of work for teachers here. I believe most of them must have superhero costumes under their shirts and ties though!

Chris: Could you tell us your experiences on the Pro Evolution Soccer series, which marked your video game debut?

Daniel Lindholm: In 2007, a person told me about a company, Dagmusic Ltd, that was having a song competition for a soccer game managed by Konami. I sent my songs there, but they weren’t picked by the main developer. However, the agency called me back and basically said that I’ve inspired them to make a new division within their company, the “Composers Pool”. I was the first one they called and of course I said yes. My very next project became Pro Evolution Soccer 2009 (Winning Eleven Playmaker 2009) for the Nintendo Wii together with my eight new composer friends! And that was my first game score.

This game was really fun to do. Basically at this time, Konami didn’t have enough money to get the proper artists or songs licensed into the game, so the eight of us at Dagmusic Ltd were assigned to write about five tracks each, “emulating” the artists they had in mind for their production. I was actually helping to figure out tracks with my partner back then, Ben Franklin. We presented the emulation-list to Konami and they green-lit us, and we divided the job between the eight of us in the company. I got to write music in the style of “David Holmes”, The Prodigy, The Crystal Method, Jamiroquai and The Chemical Brothers. It was a great way to kick-start my career. Thanks Dagmusic Ltd!

On the other games in the Pro Evolution Soccer series from 2010-2012, I was an orchestrator for other composers. I also did some real brass recordings for other artists. It was fun while it lasted and now Konami has the economy to get real artists to bring it into their games. It was a great experience to be able to help them out.

Chris: For Resident Evil 6, in contrast, you were charged with making many of the climactic action pieces. In general, could you tell us more about how this internationally-produced soundtrack was made?

Daniel Lindholm: Now, as many of you know, Resident Evil 6 at the time was the biggest and largest production investment any Japanese computer game company has ever taken on up to this point in history. I don’t know what was said at Capcom’s office, but I believe it could have been something about bringing the series to a wider audience and upping the ante on the audio-side. For the music… I’m paraphrasing here, but they simply told me: “We need that ‘Hollywood’ feeling!” So hearing this on the meeting I was excited to see where I would end up. We had a briefing together with the other foreign composer team from L.A, and the Capcom Sound Team told us about their vision and ideas, including how the gameplay mechanics would alter the music. In short: “We’d like it to be like Uncharted 2”.

Then we went through the different characters and their “instrument-palette”. Leon would have this Gothic instrumentation with very low woodwinds to create creepy atmospheres, while Chris’s campaign would have that high-tech dramatic and militaristic hybrid score. Then newcomer Jake Mueller was having this kind of rebellious, percussive Hong Kong orchestra inspired by kung fu. We also looked at Ada Wong for her high-tech spy / thriller sound. I took notes and I’d scribbled down five stars on Chris and Ada. I felt that those characters suited my style. Later, during the dinner, I told the lead-composer Mr. Narita about how I felt and he also had the same idea that my music would fit those two characters perfectly. It was a dream-match!

On top of that, we learnt how to write the music so the music programmers could implement it into the sound engine. That was a completely new experience for me, since it was no longer about writing one theme there and another one over there… instead the tracks were written in three to four segments; this allowed them to program in markers and fades to switch between different areas in the song itself! I just can’t thank the Sound Team and Capcom enough for having given me the experience and advancing my new writing skills for the interactive medium.

Chris: How did you approach your own contributions on Resident Evil 6?

Daniel Lindholm: My largest contribution? According to Mr. Narita, he said that I came up with a really nice theme for the “Neo-Umbrella” soldiers in “Neo-Umbrella Assault” track. It had that kind of heavy adrenaline-pumping combat feel to it. When I started writing that song, the pattern playing is actually inspired by John Williams. I was watching Raiders of the Lost Ark and the segment when Indiana Jones is facing off against the big Nazi under the plane was what inspired the main rhythm. And I also felt that the word “Neo”, as in “Neo-Nazi”, or in this case when a new evil entity has sprung to life as “Neo-Umbrella”, deserved that kind of menace.

But for me, the song playing during Chris’s Harrier Mission, “Aircraft Carrier – Airspace/VTOL”, was for me the most complex thing to write. Remember when I said that one song would be divided into different sections for looping and then transition into another part? Usually there would be two to four sections, however, this one had up to six different sections! Confusing as hell, but I’m so glad it all worked and I had a lot of fun writing this piece.

Chris: Resident Evil 6 and the majority of your other soundtracks you have contributed to are large collaborative efforts. What are the benefits and challenges of this approach to scoring? How extensively did you interact with the sound director and other composers during the making of these soundtracks?

Daniel Lindholm: Basically I don’t interact with the other composers who are working on the different parts of the show. I guess the producers don’t want everything to sound the same or aiming for variety as the X-factor of the project. I was pretty much on my own when writing for Resident Evil 6. But thanks to Mr. Narita, the lead-composer on the game, he was able to guide me through what they wanted without really affecting my sound. But I didn’t really have a “direct”-line with him, so Mr. Yasue Fumio (formerly Dagmusic Ltd) was a key-factor for the smooth translations between me, my agency, and Mr. Narita. It was a great experience. We actually related most of our talks without using musical terms, which meant itself that I didn’t need to be locked into a certain musical idea. We were more talking about the tension/timbre for a segment or if the piece itself should be faster or slower in tempo.

Today, Mr. Narita and I speak to each other once a year at the sound composium late-night-party that happens about two weeks before the Tokyo Gameshow. We seem to be hitting the right notes on how to work with each other. We also got a great experience on what to say and not to say when we are talking about navigating through a hard piece that was tough to write for to begin with. He was always good at explaining what he wanted and the feedback was fast and easy to understand. I’m looking forward to work with him again if the chance presents itself in the future.

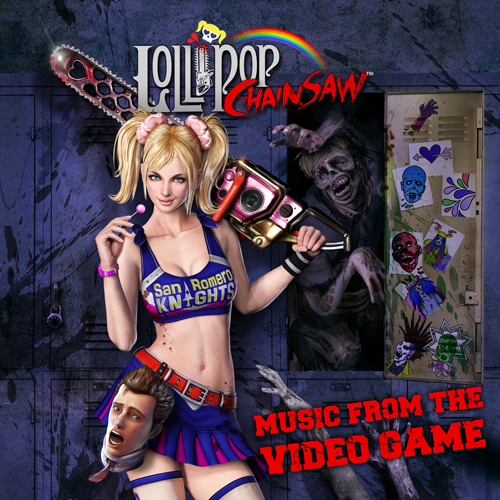

Chris: You continued your work on zombie games with Lollipop Chainsaw. What was it like to work on such a weird and wonderful title?

Daniel Lindholm: Now, Lollipop Chainsaw was an interesting game indeed. When I first was introduced to the idea from my superior, who now was promoted to Coordinator at Dagmusic Ltd, the only words he could tell me was that the game was about a cheerleader killing zombies and rainbows. I just couldn’t figure it out, but in my head I saw like an “old-school” image side-scroller like another company did with Scott Pilgrim vs The World on the PS3. Pixelated and simple. But after visiting Suda51’s game company, Grasshopper Manufacture, me and my other partner Mac Nobuka, got to see a build of the game, my mind was once again surprised by what they had in mind. It had… how should I put it… an extreme attitude!? It had such an attitude and the jokes were of such a nature that I was laughing really hard. I mean, later I heard that screenwriter James Gunn was onboard… I was in! It was corny and it was a throwback to the good old 80-90’s stiff humor. It made fun of our vision and fashion-sense from then and I could related to it really well. I just couldn’t believe it!

It was also one of the very first games where the music would change intensity depending on the enemies on the screen. But in the end, I suppose the machines were running out of memory and a more “collage”-style cutting of the music was the better approach. It really works because of the screwball humor. I was pretty much assigned to do two scenarios for it, the Viking stages and the Neon Funk stages. I had also no limit to what to compose other than to maintain the overall sound while making the tracks still sound different from each other. So everything went in, every idea from me was accepted. So once again, I’d like to thank the people at Grasshopper Manufacture for their very liberal, creative working stance. That’s why I believe all of their games are so different and fun! It was a fun project to work on.

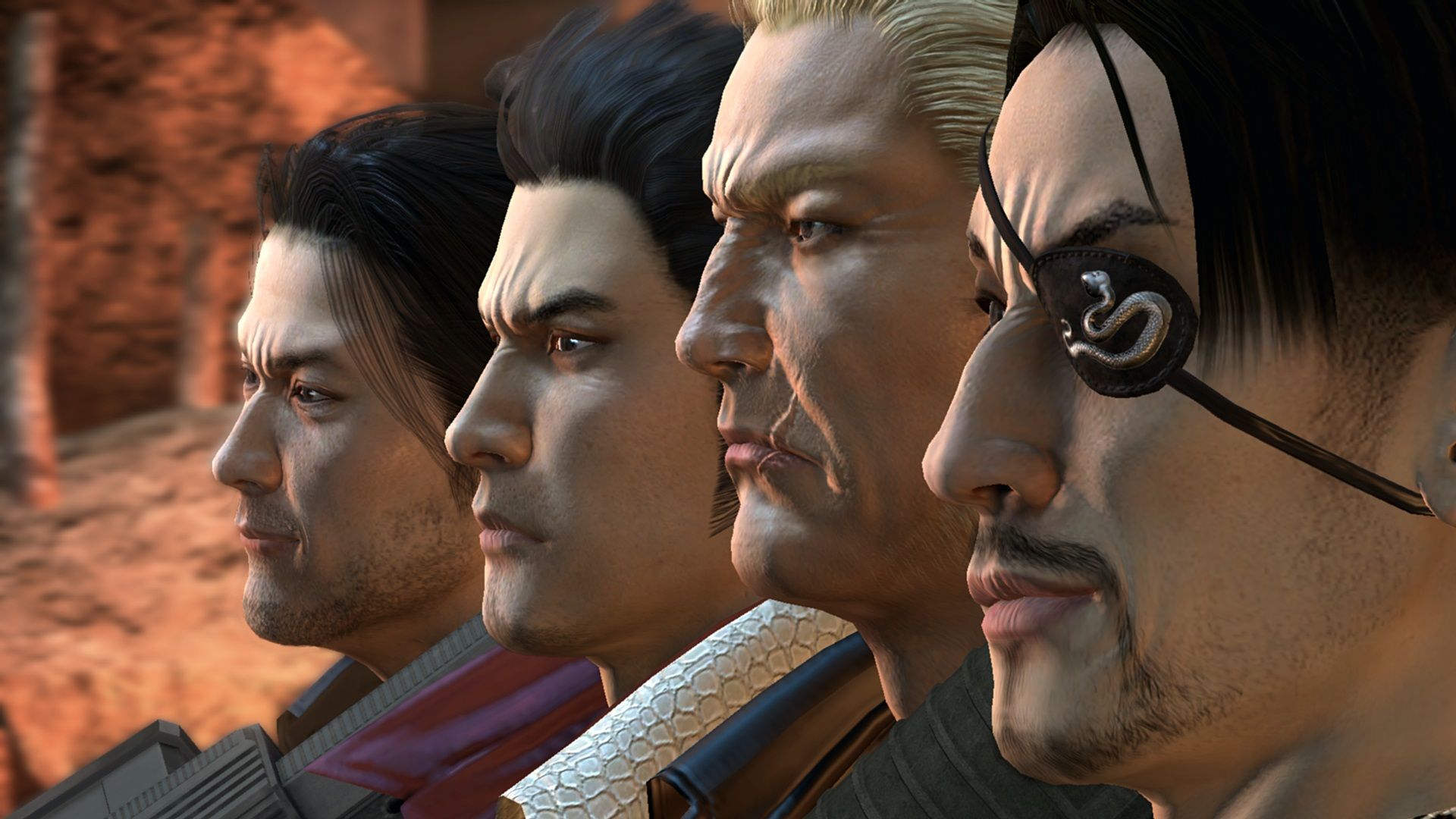

Chris: Keeping up the zombie theme, your contributions to Yakuza: Dead Souls are incredibly emotionally-charged. Could you tell us more about your work for this series? Did you immerse yourself into the scenarios while working on it?

Daniel Lindholm: I’ve played the games and I was actually surprised when Yakuza: Dead Souls landed in my lap. It was technically the second game I wrote for SEGA, the first being the ultra-cute Super Monkey Ball 3D. I was like: “How do they know I can write this dark, dirty stuff when they just had my squeeky clean, play-time music?” A huge contrast, and I was happy that I got the chance to write for them. In general, I don’t get to know much about the game and I’m only briefed very quickly about the scenario for each “game” segment that I write music for. I think what helped was my prior knowledge about the character types like Kiryu and Goro (he’s fantastic!). I think, all in all, to strive for emotion, you can’t let the computers do that for you… it needs to be done by hand. That means that I performed each instrument in one take, sorting out the best overall performances and I just keep it there without any editing whatsoever. So if you hear a piano in a track of mine, it’s the real performance.

I was assigned three tracks for Yakuza: Dead Souls. For “Sorrow”, I had no information to go on except it was a very sad moment and what they wanted out of it was hopelessness: a sense of abandonment and despair with a small hint of “hope”. This is what I would call one of those emotional tracks that I usually don’t write, because in games it’s all about the action. I was glad that I was given the chance to write this small piece of drama. It’s all about battle in “Strain”. For this score, an infected guy turns into one of the ugly zombies! I wrote this percussive, heavy orchestral track in 7/8 — both to capture the limp walk the zombies seem to have, plus create a sense of urgency that comes from being surrounded at every angle. For “Dash”, I think that this piece works well because of the tempo and where it is used. The original title for this one was “Jeep”; it was simply explained to me that the main-character gets on a jeep that has a mounted machine gun and that mowing down enemies would be “Simple FUN!”, as Goro would have put it. The temp-song I got for this one was a piece by Nine Inch Nails, but I chucked it and just concentrated on the simple layout of the instruments and timbres.

Chris: Could you tell us about your work on Yakuza: Black Panther 2?

Daniel Lindholm: For Yakuza: Black Panther 2, I finally got to work on a game that relates to the parallel universe to the original Yakuza games. When I first got my hands on it, the project name was Yakuza: Portable. I had no idea it was this game, but I did buy the first game and fell in love with it. When I later went to Tokyo Game Show and saw the cosplayers for this game, I realized how big the hype was for it. Just a few weeks later, SEGA told me (via my agent) they needed my service and I was onboard. It was a very serious project for me. I already had played the first game and came to know the main character really well and the comic-book presentation was a fantastic way to move the story forward. I tried to put myself into the mind of our “anti-hero”, now a big fighter in the illegal underground fighting ring. This is one of those few moments in your lifetime where you score a “Home-run”. My definition of home-run is that you write each and every track perfect, without any kind of revision! I actually was asked to remove one or two instruments, and that’s all! It was a great experience. Another fun fact about the soundtrack release to this game is that it was released as a very limited edition vinyl EP.

I was dealing with three tracks to this project. So far the track list have been only in Japanese, so it’s really hard to put any English titles on the album but I can tell you how I approached this project. The biggest surprise ever for me was finding that the first track you hear in the game (for the initiation fight) is my song, that I called “Anger Management”, pumping in the background while you start reading the dialogue. It really set the tone that this would be a more serious game, since the crazy adventure of Yakuza: Dead Souls. When I finished the fight and I heard the other composers work, I was blown away! I don’t know how often you get to set a “foot-print” on other people. It was an honor and my heart melted when I heard what they did. They kept my “identity” throughout the game and, until this very day, I’m very happy with the respect they paid me as a foreigner, trying to imagine what the Japanese Gangster Sound is.

The second track I I wrote was simply called “Escape”. As you can imagine, being chased by the two sides, the Yakuza and the Police, you have no other option than to run and fight your way out of Kamurocho. This track is very percussive, with small orchestral elements, bringing out the drama and seriousness of this hopeless situation. I was a little bit inspired by Sean Callery from 24 when writing this track. The last track I wrote can be translated to “Tailing the Dragon” (in Japan, the original track name was “Ryu-Tail”, given Ryu means dragon in Japanese). It was a modern noir-jazz sound with electric piano, bass, drumloops for that inner-city feeling, vibraphone, and a clean electric jazz-guitar. It was a nice touch to make this a “side-mission” track featuring a little bit of detective work by our anti-hero for once.

Chris: You’ve also contributed to the Super Monkey Ball and Samurai Shodown franchises. Can you give some insight into your work on these projects?

Daniel Lindholm: I knew about Super Monkey Ball 3D, but I had no idea it was a launch-title for the 3DS. It was one of those games where I got a temp track of something and I basically tried to emulate the tempo or the instrumentation. This was more of a World Music Experience due to that the game takes place in many different areas of the globe. Nothing too serious, but very cute! The music here was approached in similar ways to pop songs. Nothing too complex, due to the limitations and reduction of the sound-quality of the system contra the content on the cartridge. The challenge to make the game sound good on a smaller portable system. So a lot of “mini-speaker” mixing was required for this project. In the end, my music was used very little, but I got paid for my services and it’s in there! And its just blows my mind that, after this project, I went into Yakuza: Dead Souls.

For Samurai Spirits, again I was dropped in to write an attraction mode song for a Pachinko machine. Pachinko for people who are not familiar with the term is a kind of Japanese/Korean-style pinball machine with video-monitors and sometimes with a spinning roulette system and with an interactive touch-screen. I was very familiar with the old SNK iterations of the original game and the rock’n roll/ metal approach to the series. I did not have much to do and basically wrote a melodic rap-metal track. Unfortunately, people in the west will not be able to hear it, nor get the soundtrack with my song for it. I did have the honor to work with Yosh, a singer from the band SSTP (Survived Said The Prophet). I also did some rapping myself on the track.

Chris: Your soundtracks boast impressive production values, whether the filmic orchestrations of Resident Evil 6 or the contemporary sounds of Pro Evolution Soccer. How were you able to deliver top-notch products? What hardware and software do you use to create your music?

Daniel Lindholm: I think the power to produce these tracks and the way they sound lies within the digital audio workstation itself. I’ve always tried to get a DAW that has the best “Neutral” and “Flat” sounding starting point. Steinberg Cubase 6 is now running on my laptop studio, from all of my music has been written on it since 2009. I bought Cubase 6 in 2012 and enjoy it very much. The choice was easy, since I’m a PC user and Logic is no longer on the platform. Logic is great for pop songs, and has that very “clean” and “plastic” shimmer on top of the sound, but Cubase has that analogue thing that basically makes it possible to put your own identity on the tracks thanks to its neutral-stamp. With a platform as Cubase 6, buying software has been a breeze. I use a lot of Native Instruments but also loads of freeware synthezisers based on famous “game-computers”, like the Commodore 64’s SID CHIP and the SEGA Megadrive/Genesis FM synth (Yamaha).

So with the software point taken care of, let’s move on to my rig. Since I joined Dagmusic at the time, I was requested to go mobile. So I looked at a lot of laptops. I decided the best approach is to buy a laptop based on a gaming rig that usually has a seperate graphics-chip memory. I buy all of my laptops in Japan and the one I have now sports an Intel i7 Core as its main processor, 8 gig of RAM and 2 gigs of Graphic memory. Windows 7 Professional, 64-bit. The Soundcard itself is a different story. It’s actually a sampler! I wanted to make it so that, at some point in the future, I would be able to integrate an mpc like approach on live performances, and when I heard about the Roland SP-555, I was sold! Great price for this box; it’s light and boosts a lot of impressive things like the 48v Phantom Powered microphone input, line in and the V-beam (you could set a midi-command on it in Cubase if you want to do some complicated cut-off sweeps etc). But right now, it is my Soundcard thanks to its ASIO capabilities. It’s not 100% in its drivers, however the sound that comes out of this card sounds fantastic. I use the classic free software “ASIO4ALL”-driver to take care of all of my shortcomings if my machine reacts weird to the hardware of the SP-555. To end the line, it all goes out through a pair of Yamaha HS50M studio monitor-speakers. For nightly work, I also use a pair of AKG headphones, the K 271 Mk II model.

For my live instrumentation I use a Photogenic Les Paul copy guitar (19,800 yen, about 200 bucks) and a Cort Action Bass (very nice for FUNK!), a five-string fretless bass, as well as a Yamaha DTX-12 percussion module with extended capability of a kick-drum / snare and hi-hat stand. I also have my two saxophones, a Yanagisawa A-991 alto and a silver Thompson soprano. And for other “wind-based” instruments, I use an old Yamaha WT/WX11 Wind-synthesizer that works well with software supporting the C2 commands (breath controller). Other stuff I have is the Roland MC-808 for coming up with ideas offline and the STANTON.4DJ to listen to music and scratch my own tracks on it. Recently, I also bought the Novation LaunchPAD-mini for some more interesting ways of programing stuff into Cubase. All of my external gear like the MC-808/ STANTON.4DJ and the WT/WX11 goes through a small TAPCO mixer, with its line-out goes into the line-in on the SP-555. I also have a Roland XV-5050 and the relic of the past, the Roland JV-1010.

Chris: In general, it’d be interesting to hear about your experiences in game-making in Japan. How do you feel Japanese game-makers approach game production and game music compared to the West? Have you ever felt any culture clash in this regard?

Daniel Lindholm: The amount of planning that goes into these projects is so detailed that, once developers get their eyes set on the goal, they rarely deviate from the plan. That goes for those big developers. It’s only during really processor-heavy testing periods that developers might change one aspect of the game and usually sound is the big culprit (gunfire, explosions contra multi-layered music) that gets chosen to be hammered down first if the programmers can’t solve the memory problem.

I still believe that the big difference is that, here in Japan, the way they make games are almost like how they started making animation after World War II. How to save money on animation-cells? Don’t make it in 24fps and use long “in-camera panning”-shots. I feel its the same way they approach the games. Not so heavy on audio, but letting the text explain more of the overall plot. I also feel that the Japanese approach to games should be easy to get into, but is heavy on story and a lot of text exposition. In contrast, we in the west would probably let the voice-actors carry the game all the way through, like in the case of Call of Duty or Mass Effect. Here, developers use a character portrait to “drive” the story along. The storytelling is probably one of the aspects that are really hard for minor developers in Japan to do. But companies who are doing it well and have the money like Konami for the Metal Gear Solid franchise have understood what makes a game like that appeal for the rest of the world. They brought in western control and game designers when they did Metal Gear Solid 4. That game became such a hit and I could almost feel how western it felt in the way it was designed.

I think Japanese developers will take the western approach sooner or later. They are great at easy games like beat-em-ups and “bullet-hell”-arcade shoot-em-ups. Simple concepts that appeals to a very limited audience. But thanks to outsourcing of westerners into their companies, we as foreigners have the power to create content that could change the Japan’s financial revenue in the export sector of games from Japan to the rest of the world. But for now, Japan is heavily aimed at its own market and I think most game developers (not the major ones) think very small. Maybe it could also be that friends of programmers don’t look at them having a job with “real” quality and maybe are embarrassed over it; that’s why you see a lot of strange names at the end of Japanese games. Most of the developers use nicknames to not let other people know that they were involved in a game made for children and whatnot. It would probably be the same for me if I started writing music for porn! It would bring me income, but I wouldn’t be proud over it, if you know what I mean. So from that aspect I can understand why there are a lot of numbers and crazy animal-names end up there in the credits.

Chris: You are a member of two companies, Dagmusic and Attic Inc., alongside fellow Westerner Sebastian Schwartz. Could you tell us more about these companies, your role, and how you land projects?

Daniel Lindholm: Dagmusic Ltd is an agency that became known for booking live acts, musicians, performers and vocalists to television and game companies in Tokyo. They are still one of the main suppliers of actors for Japanese TV shows and computer games aimed with foreigners in mind. They’ve always been associated with having a great library of singers that Square Enix and Konami use for their games. My role in this company was that I was brought in after a big audition, which landed me a small contract with the company into their newly started “Composers Pool”. However, some companies weren’t sure if we were able to create original content and mostly only related to Dagmusic Ltd for hiring singers, not for original work. But as with every company, there is always an idea and from this “Composers Pool”, my agent started up another company that is exclusively aimed for Original Content and as a Production House. That company became Attic Inc.

Attic Inc. itself consists of my agent, Ms. Chizu Iwaki from Dagmusic Ltd, and Mr. Kenji Nakajo, a sound designer from Tecmo/Koei Games. So I basically was headhunted by them and I was totally onboard with a company looking for original material. Basically I keep on working as before, but the jobs are more a creative and brough in a little bit more variety. Not only have I been able to write music, but I also work as a lyricist. So I’ve had a lot of different missions, among them to write lyrics for Gran Turismo 6!

I decide the jobs I want to take based on what music skills I have and of course what I want to do myself. During the interview, I tell them about what I would like to do. It seems like a new game version is developed in a cycle of four years. So I keep looking at the calendar and wishing for something cool in the near future. Usually my agent hunts for clients, showing them demo-reels or an out-take of styles of songs we write and present them for the client. Then the clients choose “who” will get the job. So even if we all work in the same team, we still have a little bit of competition. But usually these days, rarely anyone gets to make music for a whole game by themselves, compared to western game companies who hire only one composer for continuity reasons (Lorne Balfe and Jesper Kyd for example). Everything is micromanaged due to the heavy deadlines, and that means splitting up jobs is the faster way to get things done. Time is money in this country. 😉

Chris: Outside of video games, you have worked for clients such as Panasonic, Disney, and cellphone manufacturers. Could you tell us some of the highlights of these works? How have they tested your versatility?

Daniel Lindholm: In all cases, it has been a mixed bag. I’ve worked on everything from cellphone signals in MIDI/Audio form to on-board music content for media players (Panasonic) to commercials. These experiences have had me put on practically everything from the producer’s hat to those of the re-arranger and orchestrator. I even got to write Swedish lyrics on a 12 hour deadline before a commercial aired. Very exciting and crazy at the same time! So it has practically tested me on all fronts. I think I get these jobs because of my ability to quickly “re-position” the production I make based on a request, or if an idea they initially had was changed and turned 180 degrees.

Chris: We’re interested to hear about your future plans. Do you intend to further pursue game and film scoring? Has Japan become your home now or will you one day return to the West?

Daniel Lindholm: You usually hear the story about film composers going into scoring games and therefore we have some of the best working composers in the industry. That’s almost half the truth. Some of the music I do hear from these composers actually is not part of the interactive experience in the game, but usually it’s just another score for cutscenes where the music takes place or a general simple loop that would play in one place. So I think, working from the other end, I have a little bit of the upper-hand when it comes to writing cinematic music in the adaptive music realm that exists quite heavy in the adventure/action genre. Jesper Kyd did exactly this. He went from writing music to the Hitman games and is now also a film-composer in his own right. So right now, I’m just building up my library of music and looking around for work anywhere on this planet.

So my wish for the future is that I probably will end up in Los Angeles, helping people out at the music production houses like Hans Zimmer’s “Remote Control” or an assistant somewhere else. But if I get the chance to score a movie, I’m not foreign to it since I write a lot of scores on my demos synced to real movie scenes. It’s a time-consuming technique that I keep on finetuning until the day arrives. It’s not easy, but it will provide a good cushion when you’re looking around for jobs in both realms. Games want interactive/adaptive cinematic music while movies want to have something more “static” and paced these days. It seems like the roles have switched on the mediums actually.

The movie-scoring thing seems a little bit far away, so the closest thing I’d like to do before I move away from Japan would be to write music for Tekken and Dead or Alive. Maybe another Yakuza title and if the opportunity to write for Metal Gear Solid or Final Fantasy shows up, I’m there. Long shots, but very possible thanks to my agency. So in general I’m longing more for the film-medium and balance it with games. Say like 70 – 30.

Chris: Many thanks for your time today, Daniel Lindholm. Is there anything else you would like to say about yourself and your works? In addition, is there any message you’d like to leave to readers around the world?

Daniel Lindholm: The best tip for all of you out there wanting to write music for games is to be your own worst critic. Second of all, criticism isn’t there to beat you down. It’s there to bring you up to a higher level. The game industry is not a one-man show. It’s about cooperation. So in the beginning it will be tough to handle the “feedback”, but it’s nothing personal. Just try to do the best you can to please the client and you will have the chance to get onboard on more exciting projects! Watch movies, listen to scores. Analyze and try to replicate techniques. Download trailers and practice writing music to picture. To have music presented together with a visual elements will bring a better impact when showing your work to agents and they in turn will use the same material to present you as a candidate for the clients. And finally, NEVER GIVE UP!

For all of you readers who would like to know more or ask me questions, please follow me on Twitter. And if you like to listen to music, follow me on SoundCloud and listen to my video demos and scores on YouTube on my new page and old page. Thank you for all of these very interesting questions! Cheers! Sincerely yours, Daniel Lindholm

Posted on June 27, 2014 by Chris Greening. Last modified on June 27, 2014.