Masanori Adachi & Hirofumi Taniguchi Interview: A 25 Year Collaboration

Masanori Adachi and Hirofumi Taniguchi have collaborated for 25 years. The composers first worked together at Konami on Madara 2 and then went on to create diverse experimental scores for numerous titles as the Thelonious Monkees: Moon, U.F.O., and Endnesia among them. While the artists have focused primarily on numerous own projects in recent years, they’re reunited to start penning a solo album.

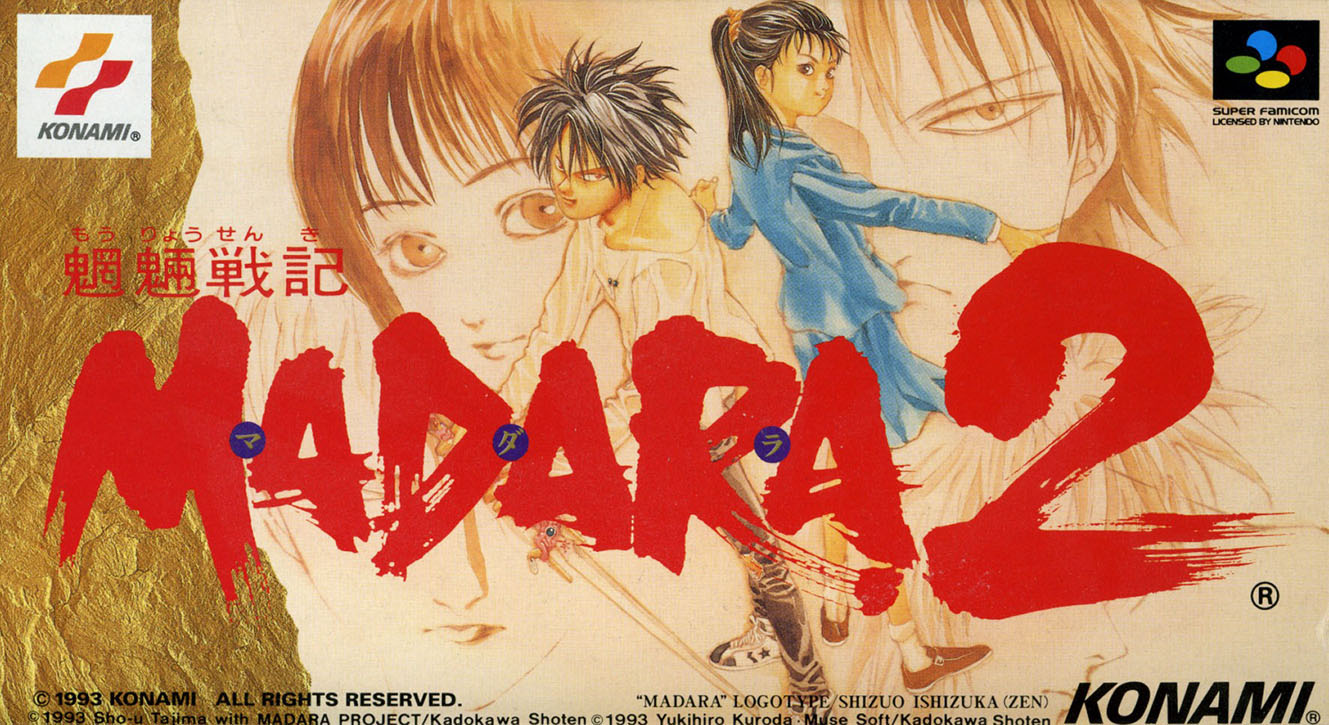

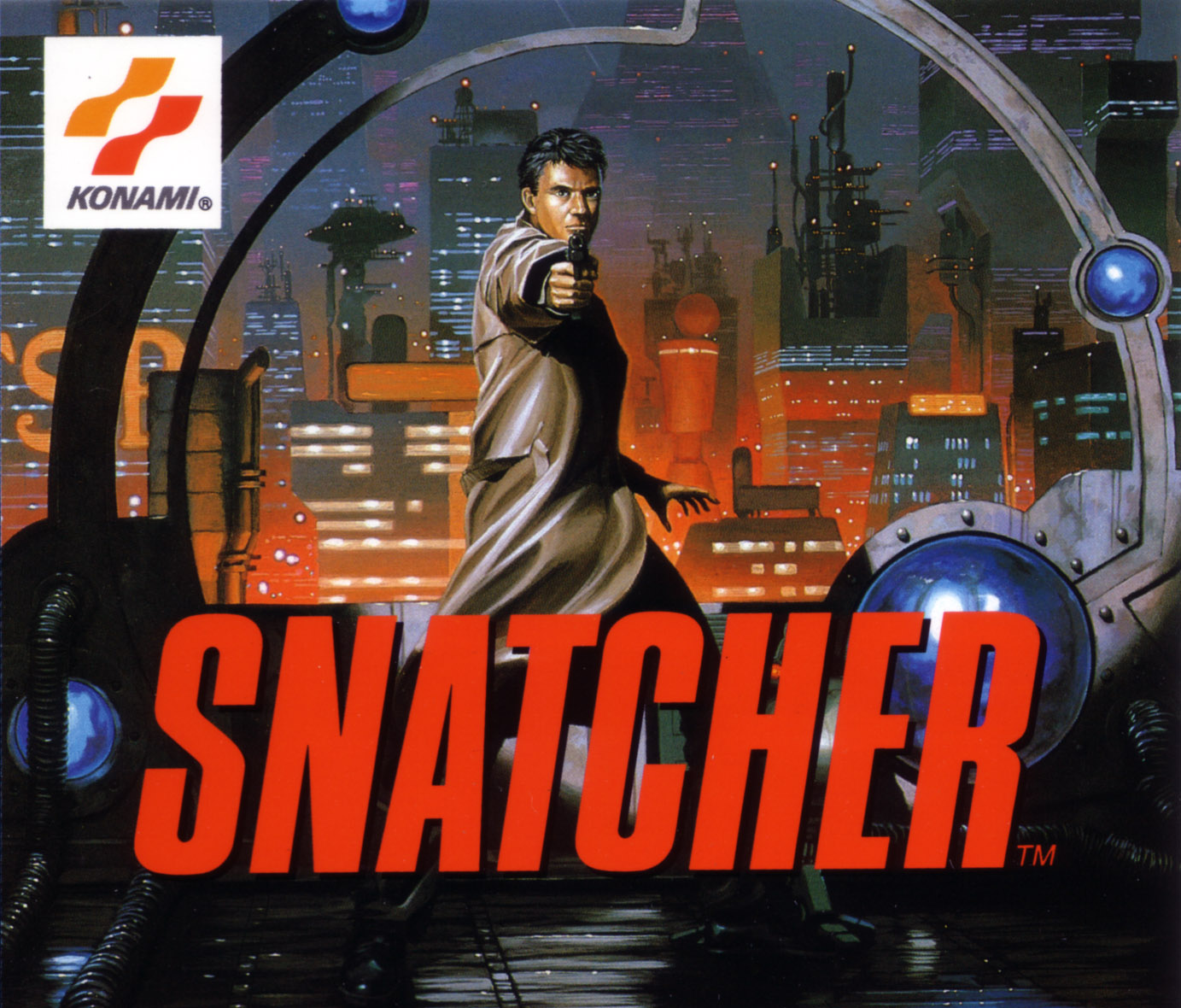

In the first part of this interview, Adachi and Taniguchi discuss their musical roots and first game projects. They focus on their work for several key franchises such as Castlevania, Contra, Suikoden, Snatcher, and Madara. Along the way, they provide revealing insights into the musical and technical processes of sound creation at Konami, as well as the collaborative spirit of their sound team. In the second part of this interview, led by Leon Staton, the artists discuss their post-Konami works for Love-de-Lic and beyond.

Interview Credits

Interview Subject: Masanori Adachi, Hirofumi Taniguchi

Interviewer: Chris Greening, Leon Staton, Quinton Kablon

Translation & Localisation: Ben Schweitzer

Editor: Chris Greening

Coordination: Don Kotowski, Miki Higashino, Chris Greening

Interview Content

Chris: Masanori Adachi and Hirofumi Taniguchi, we appreciate you both taking the time to talk with us today. The two of you have been bonded through various companies, projects, and a band called the Thelonious Monkees for 25 years now. What is it like to sit down today and discuss your collaborations? What do you think has kept you so closely associated over the years?

Masanori Adachi: First and foremost was the fact that I loved the music Taniguchi created and his sense for arrangement. Since Coloball 2002, we’ve taken a break from collaborations as we’ve both been busy with our own individual projects, but since about last year the talk of “let’s make an original album” finally became a reality, and we’re working on that right now.

Hirofumi Taniguchi: The name Thelonious Monkees gained a little bit of attention through Moon, but heading into the 2000s we’ve really been focusing on our own separate works and so we haven’t been active as a group. Recently, though, our schedules have begun to overlap more, and I think it’s great that we’ve been able to start working together again.

Chris: Before we talk about your specific works, we noticed that you both have produced plenty of diverse and experimental music over the years. Could you each tell us more about your respective backgrounds? How did you develop eclectic musical tastes?

Masanori Adachi: I think it was in my teens that I started to enjoy listening to music more than anything else. I would divide music into what I loved and what I disliked more on the basis of whether or not it had phrases and harmonies I liked, even within a part of a song, rather than on the basis of genre.

So more than individuals, I would like this part of this song. Listening to a cassette tape I recorded at the time, it isn’t dedicated to any particular genre and you’d find commercial songs, TV drama themes, or soundtrack music mixed together.

Hirofumi Taniguchi: My father was a classical fan, so there would always be classical music playing in the house. That said, I was far from a music fanatic at the time. I wouldn’t know the composers or the names of the pieces, just that when this phrase opened the piece, I learned to be able to hum the part that came next. Sometimes I had fun singing the various harmony parts.

At that time, I never really had any interest at all in popular songs or singers, but it came as something of a shock to learn from my older brother that there were rock bands out there who created and performed their own music. I had always thought of music as being something passed down traditionally, like folk songs. My brother’s influence led me to start listening to The Beatles. At the same time, I began to create my own songs and pieces as a hobby, using multi-track recording to capture them on cassette tape. I was something of a child Todd Rundgren.

In middle and high school, too, my obsession with music continued to escalate, but I was really only working in a rock band style. I was the type to listen to a single band’s albums over and over, even hundreds of times, until I could sing every part of every instrument without the record. When I went into college, I began to develop a conscious interest in classical music as well. I know a lot of classical and neoclassical music quite well, but I simply didn’t feel the freshness in them that I was looking for. Instead, I have always love listening to orchestral music from the 19th and 20th century. At that time, I was connected to a prog band that made use of lots of odd meters. I think I was searching for some kind of individuality in music.

Chris: You both entered the game industry as musicians at Konami’s Tokyo branch. Could you elaborate on what led you to join this company? What was it like to work alongside musicians such as Miki Higashino, Tappi Iwase, and Taro Kudo back in the day?

Masanori Adachi: Even before I entered KCE Tokyo, I had been providing music as a part time worker. If you added them all up, I think I created about 500 or so tracks. I don’t know if and how they were all used. It seems that all of them, or at least a selection of them, were used in games released on arcades or on the Famicom Disk System. Specifically, I can think of Battlantis, Contra, Devastators, the Castlevania series, Devil World [Dark Adventure in the US], Koi no Hot Rock, etc.

After that I moved to Tokyo, and KCE Tokyo had just been founded so I continued to reach out to and work with them. Following my work on arcade games, I ended up being assigned to their Super Famicom development division. It was the early days of the Super Famicom era. Inspired by what people from other companies were doing with the system, I decided to try surprise them all with something new. So there was a kind of friendly rivalry where we all tried to outdo each other.

I met Higashino-san, Tappy, and Kudo around that time. I enjoyed working with all of them. We all worked on our own projects, of course, but we would help each other out with bits of arrangement or fine-tuning here and there, so it was really a free kind of give and take.

Hirofumi Taniguchi: In college, I was looking at a music magazine owned by someone from my dorm who sat next to me in the study room, and I came across one page with an article that said “hey, we’re hiring” in a very joking manner. It was an article about a search for composers for Konami’s sound team. I passed the test and entered the company right after graduation.

At that time, there were only two new graduates working at Konami’s Tokyo branch. Higashino-san’s seat was very nearby, and she was always friendly. I would occasionally play board games with Kudo in the evening on the weekends, but we didn’t really work on the same team. Tappy had played drums in my prog band, Il Berlione, and I got to know him much better through that than through Konami.

Chris: Adachi-san, one of your most memorable works was the soundtrack for Super Castlevania IV. What inspired you take a more cinematic and ambient direction on this release compared to previous Castlevania soundtracks? Did you ever expect tracks such as Simon’s Theme to become so iconic?

Masanori Adachi: At the time of Castlevania, I was working on techno and ambient music together with the people who ran a techno event called Voice Project. I think that turned out to be very influential.

Unfortunately, at the time the reception to the soundtack had been extremely negative. The same was true during production. Back then we would do internal evaluations, where people would clearly express whether they thought something was good or bad. I was grateful that the people who were in charge of making decisions let me keep creating whatever I wanted to the very end.

After the game’s release, the soundtrack went completely ignored by fans who had loved the series’ music up to that point. I lost a lot of my self-confidence, but afterwards I received an award from a magazine called Edge, so I felt that it paid off in the end. As for Simon’s Theme, I had no idea that the track would become so iconic.

Chris: Taniguchi-san, you were also active as a sound designer on a range of Konami titles, notably the Contra series. What did you learn about sound design from these early experiences? Can working on sound effects be as satisfying as composition roles?

Hirofumi Taniguchi: When I was a new recruit, I had to create a whole bunch of sound effects for the Super Famicom Contra game. It’s not very well-known, but I also wrote a piece of music for Contra: Hard Corps.

With the Super Nintendo, we were still in the era of using various timbres on musical scales for sound effects. When arranging those scales, there would be a large disparity between the scale constructions that came out well and those that came out poorly. Under those conditions it was difficult to find sounds that made an impact or that were creative in some way. Today people will create sound effects using sound effect CDs, but back then it was closer to music creation.

I think of both composition and sound design as being parts of my life’s work. With video games, the sound effects often have a better chance of making an impression on the ears of players, so I wouldn’t point to either as being intrinsically more satisfying.

Chris: Adachi-san, you also contributed to numerous other major soundtracks during your time at Konami, including Aliens, Axelay, Tokimeki Memorial, and SD Snatcher. Looking back at all these productions, which do you consider your finest achievements and why?

Masanori Adachi: I suppose the projects I was most deeply involved in at my time at Konami were Aliens, Escape Kids, Madara 2, and SD Snatcher. The development team for Aliens was right next door to the Qarth team, which I felt made for a chaotic but enjoyable development environment. After both of those projects were completed, the teams merged to create Escape Kids, and my memories of that project are characterized by an open, anything-goes philosophy.

I actually didn’t write a single piece for it for Madara 2. Instead, I would give my ideas to great composers like Higashino-san, Tappy, Taniguchi, and Aki Hata-san general ideas about presentation so that this kind of music would play in this place, and I would work on the sound quality and arrangement to ensure that there was a feeling of consistency.

With Snatcher, we had entered the era of digital processing with the release of ProTools, and game hardware had also been evolving, so there had been advances in the data capacity allowed. Together with movie scenes came the ability for streaming playback, and this made it a transitional era for composers as methods of composition also changed greatly. There was a steep learning curve, from sequencing technology to sampler banks to engineering technology.

My own department didn’t have much in the way of a budget, though, so we at KCE Tokyo had to create a studio using whatever we could scrounge up, like when we used egg cartons for sound proofing. With SD Snatcher, part of our job was to remix the music that had already been provided by Furukawa-san. I asked Kida, Yamaoka, and Nakamura-san to work on the remixes.

Chris: Taniguchi-san, you made a mark on Konami at a later date with the soundtracks for the RPGs Madara 2 and Suikoden. What can you recall about from the development of these ambitious soundtracks? How did the shift from the Super Famicom to PlayStation influence your composition approach?

Hirofumi Taniguchi: At the time, I had my own regular projects that I was heading up. For the two games you mentioned, I was really more of a person from another division that provided music because it was requested. With Madara 2, I was in sole communication with Adachi-san, while on Suikoden it was Higashino-san. Hata-san would also participate in meetings, so I met her through that. Other than that, there really wasn’t any horizontal interactions on these projects. So when I saw the other people involved at meetings, they were really more like acquaintances to me.

I think I wrote something like two tracks for Madara 2. I created a demo for a dungeon theme, but when it was ported over to the Super Nintendo the atmosphere hadn’t changed much at all, so it worked out really well. The other track was a boss theme which I had originally created for myself, but when I played it for Adachi-san, he said that he wanted to use it.

However, there were a lot of problems when porting that track over to the Super Nintendo sound chip, from having to cut down the number of voices to being unable to reproduce the correct timbre, so I remember that the atmosphere ended up changing completely. Even so, the altered version would have its own unique color… Because the specs on the Super Nintendo were limited, the expressiveness of playback would end up exerting a significant effect on the quality of a track, so when you composed, you had to anticipate a less than perfectly satisfactory result.

With the track “Narcissist’s Waltz”, which I wrote for Suikoden, there were far fewer limitations on the sound, so I was able to get all of the nuances of expression I was looking for and produce a very satisfying result. Higashino-san had asked me to write something that was as crazy as I could possibly write, but my first attempt actually ended up being too crazy, so I remember her asking “just work on it a bit more,” and I re-worked the piece. I’ve been very happy to see how many times the piece has been arranged throughout the series, even after I left Konami.

Posted on February 5, 2017 by Chris Greening. Last modified on February 5, 2017.