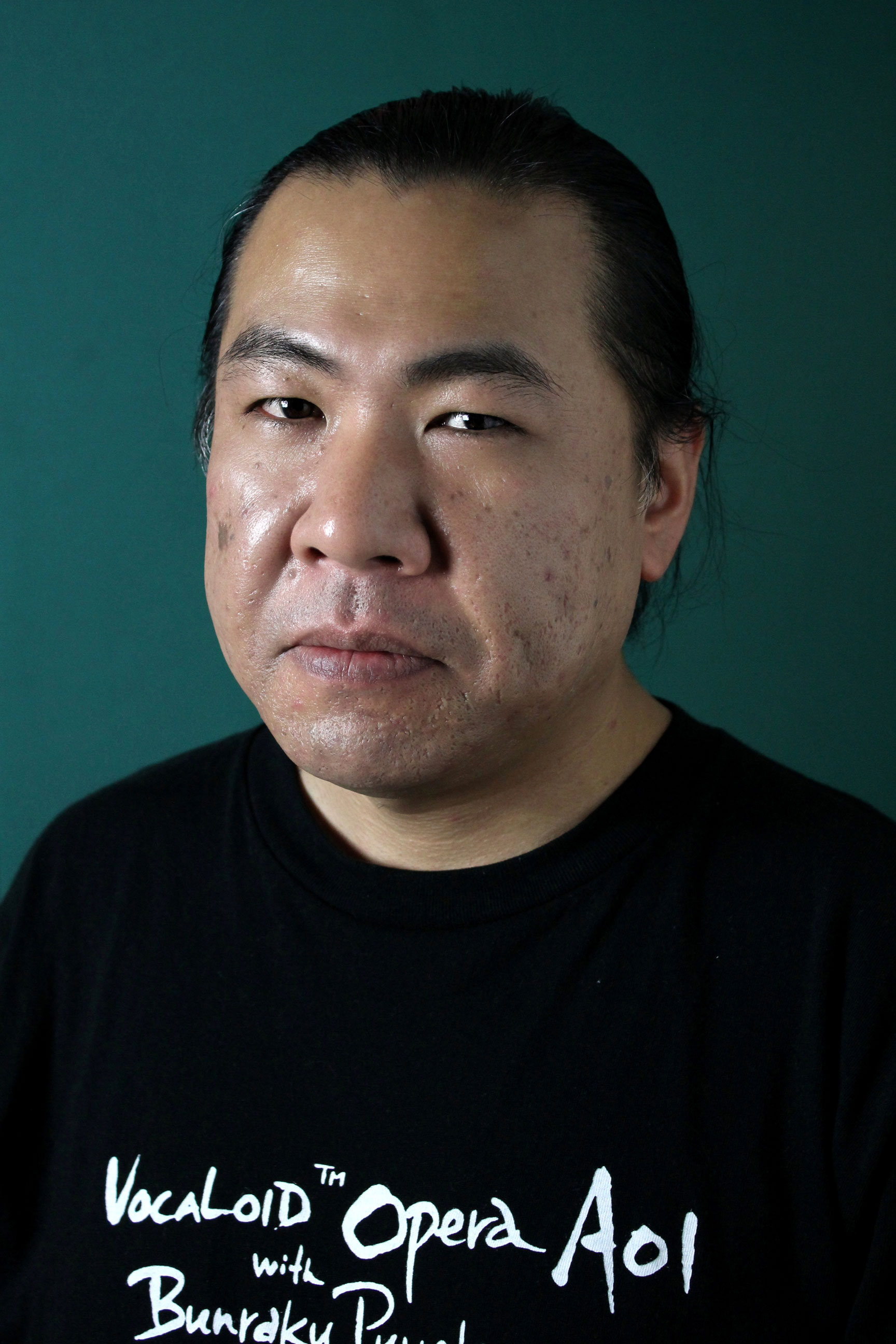

Hiroshi Tamawari Interview: Switching from Games to Opera

Hiroshi Tamawari helped to define the sound of Konami’s PlayStation era, with his leading roles on Vandal Hearts, Azure Dreams, and Vandal Hearts II, as well as his memorable contributions to the Goemon, Twinbee, and Suikoden franchises. Since his departure from Konami at the turn of the century, Tamawari has worked exclusively outside the gaming sector, handling everything from scoring commercials to translating musicals.

His latest creation comes in the form of an unorthodox opera entitled VOCALOID Opera AOI, a live musical that features classic Japanese bunraku puppets singing in Vocaloid over music influenced by modern techno and traditional Japanese stylings alike. A Blu-ray and DVD of the performance is slated to release worldwide on May 21, 2015.

In this indepth email-based interview conducted with the assistance of his wife Akiko, Hiroshi Tamawari talks about his time at Konami, detailing the challenges of composing and implementing music on PlayStation. He subsequently goes into immense depth on his innovative VOCALOID Opera AOI, and how it is influenced by multiple art forms, cultures, and eras. Along the way, he reveals the reason why he left game music in favour of stage performances and speculates on whether he might return to game music through an arranged album or new score in the future.

Interview Credits

Interview Subjects: Hiroshi Tamawari

Interviewer: Patrick Kulikowski, Chris Greening

Translators: Tomoko Akaboshi, Gerardo Iuliani

Editors: Patrick Kulikowski, Chris Greening

Coordination: Patrick Kulikowski, Akiko Tamawari

Interview Content

Patrick: Hiroshi Tamawari, thank you so much for doing this interview. First of all, could you tell us about your musical background, education, and influences? What led you to becoming a video game sound creator?

Hiroshi Tamawari: While I was preparing to take the admission test for a private middle school as a child, I got a cassette from my parents who told me that “listening to classical music while I studied would be good for me”. I didn’t really have any interest in music until that point, but started getting more interested, as that tape featured songs from many TV commercials and orchestral arrangements of famous folk pieces from around the world.

During my student days, I played the trombone and served as a director of the wind instrument and orchestra clubs of my school. In addition to classical music, I also listened to pretty much every FM radio program broadcasted, and bought and played scores for music of all sort of genres.

I gradually began gaining an interest in composition and arrangement during my teenage years. I began studying music theory books, such as Orchestration written by the Japanese composer Akira Ifukube. By the time I got to high school, they were already putting out relatively cheap hardware sequencers for sale, so by using them in conjunction with electronic keyboards, I was able to start composing.

It was also around that time I went to watch the musical Les Miserables, which left a very deep impression on me. So during my time at college, I participated in a troupe that made their own original musicals. For their productions, I was in charge of writing the lyrics, composing the songs, and directing the performances.

Patrick: Some of your earliest projects for Konami were on the Twinbee franchise. How did you come to join Konami? Could you tell us how approached the Twinbee series’ puzzle and RPG spinoffs?

Hiroshi Tamawari: After I studied Law at college, I sent in an application to join Konami’s sound department. I was finally accepted after they examined my demo tape and interviewed me.

Twinbee Taisen Puzzledama was the first project I worked in after I joined the company. I think I mainly made arrangements of pre-existing songs from the Twinbee series though. Since I’m pretty bad at composing music that is meant for a general rather than specific context, like is often the case for puzzle games, I ended up being a lot of trouble and my pieces were rejected many times.

I was tasked with creating all the compositions for Twinbee RPG. As the Twinbee series already had an established image, it was pretty difficult to come up with melodies that fit with this. I used the internal sound fonts for the entire extension of the soundtrack, so working in this game gave me the chance to learn many things about how to work with them.

Patrick: You apparently worked on five tracks for the first Suikoden on PlayStation. Please share your experiences working on this influential project. Can you recall which tracks you composed?

Hiroshi Tamawari: The music for the first Suikoden allowed streaming and direct playback of the waveform data that was recorded on the CD-ROM. Thanks to these specifications and the fact they allowed us to make music with as much variety as we wanted, several composers ended up taking part in the project, the main one being the composer and sound director Miki Higashino-san. I had two main responsibilities for the game: the world map music and music for some additional scenes.

While much of the game’s music was streamed, the music for the world map had to be played back through the internal sound fonts, as they required having the map data read from the CD-ROM’s contents. However, pretty much everyone in the composer team were in teams that developed for the Sega Genesis right before this project, and thus there was next to no one who knew how to work with the PlayStation’s internal sound fonts. In fact, I think this game was the very first one in which Konami used the PlayStation’s internal sound fonts for music creation, not to mention one of the first in general [Editor’s Note: The game was released in 1995 in Japan].

But I was assigned to a PlayStation development team before they did [Editor’s Note: For Twinbee Taisen Puzzledama], so I had a little experience in working with its sound system. Since Higashino-san had already composed the melody we would use as the game’s main theme, we ended up making the world map music as a variation of that melody, which could be interweaved with the finished main theme.

In terms of my other contributions, while several new scenes were added into the game, there were no people who had enough time on their hands to make music that fit them. So I do remember I composed a few of them, but I don’t know exactly which songs these were, as I was asked to make them as fast as I could.

Patrick: You first gained the attention of Westerners through your excellent soundtrack to Vandal Hearts. Could you describe your composition and production process for this game? What kind of software did you use for the synthesized orchestras?

Hiroshi Tamawari: In contrast to Suikoden, the entirety of the music for the Vandal Hearts games used the sound fonts of the original PlayStation. The main director demanded that we didn’t access the CD-ROM at all because the game would need to constantly read other data like the image files. That said, while the music ended up being entirely made on the internal sound fonts, there were a few scenes in which no image files were being read. For these, we could call up waveform data directly from the CD-ROM in order to play the sound effects. I wasn’t in charge of them though, as we already had a sound effects specialist on board.

When I worked on the original Vandal Hearts, I didn’t really have much knowledge on how the PlayStation’s internal sound fonts worked, so everything was done through trial and error. But when I worked on Vandal Hearts II, we had several development tools prepared for it, including some that were exclusive to the company staff, which made it far easier to try to experiment with the music.

Patrick: Could you elaborate on how you manipulated the internal sound fonts to achieve such rich sounds on Vandal Hearts II?

Hiroshi Tamawari: The PlayStation’s internal sound fonts are played by using a sampler system in which the pitch is changed while the compressed waveform data undergoes decompression. Since the sounds of the samplers and synthesizers (like Proteus 2 made by E-mu) are imported as waveform data, we edit them as sample data that will be read by the PlayStation. As the sample data requires very little memory space, we can create loops in almost the entirety of its waveform data. I remember that I also made loops for the cymbals and drums.

I remember that, while the PlayStation internal sound fonts could be played at the 44.1KHz sampling rate that is used by normal music CDs, that would make the sound too stiff. That was the reason why we lowered the sampling rate to 38KHz, which also helped us to save memory space. Furthermore, we also applied digital equalizer processing to the samples we utilized, and we tuned the sound quality in order to give it the same orientation and depth an orchestra would naturally have. I remember it took us about two full months to complete all the sample data editing work I just described.

As for the making of the sequenced data, we did so through Logic made by Emagic Ltd. (now owned by Apple), which was distributed within our company. As the PlayStation uses a MIDI conversion system for its instrument data, we ended up making the sequences for the music while playing the MIDIs from sequencer programs and such executed through a PlayStation emulator. And I have to say I still continue using Logic to this day.

Vandal Hearts Original Soundtrack (Konami, 1996; left); Vandal Hearts II Original Soundtrack (Konami, 1999; right)

Patrick: Vandal Hearts II‘s music was a very big upgrade in comparison to the original Vandal Hearts. What constituted this giant leap in audio quality? How did this influence your compositional approach?

Hiroshi Tamawari: Music-wise, the score for the original Vandal Hearts was jointly composed by three people. I was still a rookie back then, so I participated under the lead of the two people that were my seniors at the workplace [Editor’s Note: Miki Higashino and Kosuke Soeda].

As for Vandal Hearts II, I was chosen to compose the entirety of its score after I asked to handle it alone. Thanks to this, I was able to much more tightly knit the relationship of the main theme and its variation between all the songs. I created many theme variations for the development of the story, and integrated many core themes and leitmotifs so that they would call to each other. For example, the prologue song repeats an ostinato (E-F-B) for its duration, which also corresponds to the leitmotif for the enemies. I placed variations of this sound pattern in several of the battle songs that can be heard in the game. This particular point is the largest difference between the approaches that were taken for this game and for the music in the original Vandal Hearts.

I also made the music match the speed at which the game’s text advances. The game waits for a bar to repeat and uses this as a signal to display the next line of dialog and the next bar in the song. As those who are familiar with the scores for musicals should know, the lines said by the characters during a play advance in real-time according to the timing given by the music cues. For matching the speed at which the players cleared the text boxes in Vandal Hearts II, I made several passages that develop sequentially without the music getting interrupted. This was thanks to the sound programmer making a special program for this purpose.

And one more point is that I tried using musical expression methods that hadn’t been used in game music up to that point. For example, the sound of the windmills spinning, the cries of the bugs and nightingales during the evening, the bewitching sound of the wind blowing through the windows, and the sounds of the waves and the seagulls at the harbor… All these sounds weren’t used as sound effects, but instead integrated into the songs themselves, which is a method of musical expression that’s widely featured in the music for operas and ballets.

Patrick: I was always fascinated by your dynamic battle themes in Vandal Hearts II. I notice a style very reminiscent of Russian composers like Igor Stravinsky, but there’s also a lot of Spanish flavor with the use of castanets. Could you elaborate on your influences?

Hiroshi Tamawari: Vandal Hearts II‘s story is themed around an ethnic conflict. Since it’s a story about several fictional cultures, at first I didn’t really know how I would express it through music. So while it’d be very simple to do something — like say give culture A Russian-sounding music and culture B Spanish-sounding music — that’d take away the fictional element these cultures were supposed to have. Music is importantly a partly cultural element, so if I took this approach, the music would end up echoing the cultures from the real world regardless of what I did. So while obviously it had to have ethnic elements, I needed to make music that didn’t resemble those produced by any real-world cultures.

So I kept in mind the classical music that was composed in the core countries of Western Europe: Germany, Italy and France. I also did the same for the classical nationalistic music composed in the countries around them: those countries took influences from Germany, Italy and France and used them to produce their own kinds of music. To give some examples, these are the kinds of music I referenced:

For the music from Germany, J.S. Bach and Brahms.

For the music from Russia, Stravinsky and Khachaturian.

For the music from Spain, de Falla and others.

For the music from Hungary, Kodály and Bartók.

For the music from Czechoslovakia (Moravia), Janáček.

For the music from Scandinavia, Grieg, Sibelius and others.

And from the Orientalism music, I referenced pieces like Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Scheherazade”, Ravel’s “Rapsodie espagnole”, Respighi’s “Belkis, regina di Saba”, and Prokofiev’s “Scythian Suite”.

Only by separately imagining all these kinds of music, and possibly mixing them, could I express the image of a multicultural fictional world.

Twinbee RPG Original Game Soundtrack (Konami, 1998; left); Other Life -Azure Dreams- Original Game Soundtrack (Konami, 1997; right)

Patrick: Would you consider Vandal Hearts II your favourite game project?

Hiroshi Tamawari: Actually, Azure Dreams is the soundtrack I like the best from all the ones I made during my time at Konami. This was the project I worked on between Twinbee RPG and Vandal Hearts II, and I was in charge of composing its entire soundtrack too. Since the story took place in a desert city, the director told me he wanted Arabian-style music for it. As I studied the music from the Arab countries, I was able to make all sorts of eccentric songs. I also made the melody that I used as the main character’s theme to receive variations depending on how much the player advanced through the scenes for the battles that take place within the tower, which serves as the core of the game.

Patrick: Also during your time at Konami, you worked on the fighting game Lightning Legend and Ganbare Goemon: Space Pirate Akogingu.

Hiroshi Tamawari: Lightning Legend was made as a collaboration between me and another composer. The sound director told us we could make its music however we wanted, and that’s what we did.

I was asked to make the score for Ganbare Goemon because the main director wasn’t satisfied with the demo tapes that several composers made for the game. I remember being told it was okay right away when I decided to make it with Ryukyu-styled music. After that trend was decided, I think the other composers that were originally chosen to work in this game began to make other songs.

Patrick: You left Konami after completing Vandal Hearts II to pursue a career as a non-game musician. What made you decide to leave Konami and the videogame industry?

Hiroshi Tamawari: It’s because game music has too many battle tracks! There are always demons inside the enemies, people exposing their ambitions, and a need to always fight something. However, fighting isn’t everything there is to the world: there are also moments shrouded in peace, love, and fun, which are what push these ambitions back and allow us to bear with the sadness. I didn’t think it was very good for my own music to lean solely towards fighting. At the same time, I strongly started thinking that I wanted to try out making music for the musicals and operas I was so interested in since my college student days.

Patrick: What kind of work have you done since leaving Konami?

Hiroshi Tamawari: After I became a freelancer, I staged an independent musical version of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Match Girl, translated several Broadway musicals, and even composed and wrote lyrics for some commercial musicals. In the last few years, it’s been pretty popular to publish internet songs made with Vocaloid (singing synthesis software by YAMAHA), so I took the chance to start making lyrics and compositions for official Vocaloid demo songs. And on a related topic, I’ve also published a book that explains how to use the Logic Pro X and Vocaloids, which is available here.

Patrick: What interests you about Vocaloid? Where do you stand on using them compared to human voices?

Hiroshi Tamawari: Synthesized voice technology is a field that is quickly developing thanks to increases in the processing power of PCs, and I think it’s going to develop even further in the future.

However, I really don’t know if the people that make music using them, or their listeners, will actually respond well to voices that don’t come from an actual person [Editor’s Note: Vocaloid voices were created by taking voice samples from seiyuus, e.g. Hatsune Miku is based on voice samples from Saki Fujita]. After all, the performers and the audience tend to prefer more realistic voices that sound like an actual human singing. I think that understanding this trait — and using technology to create a machine that sounds exactly like a human does — is something that fascinates a lot of people.

But if we’re talking about genuine musical expression, if anyone wants a real voice it would be better to just make an actual living human sing, as there’s really no point in making a performance with machines instead. So I think it’s more possible for expression through synthesized voices and their reception to develop in an entirely different direction from real voices. I don’t know yet if they’ll come up with mixed performances of actual humans and synthesized voices singing together, or if they’ll make entirely new voices for the synthesized ones. The possibility of giving the synthesized voices a use as a new instrument created in this time period is something I have to think deeply about as a composer living in the present era.

Patrick: Your most recent project is VOCALOID Opera AOI, a Bunraku puppet show that blends two very different musical styles together: Japanese folk music and vocaloid. What was the inspiration for creating this?

Hiroshi Tamawari: We have a type of masked song-and-dance traditional theater here in Japan called Noh, which served as an inspiration in great part for Opera AOI. Noh has a very stylized play structure, so its plotlines have the same general outline in many programmes. For example, a play could be something like a real-world person (generally a monk) coming to a certain place and meeting something that appears from the underworld (a Kami, soul, demon or vengeful spirit). I was wondering how I could express with current methods the mysterious, or rather magical, images Noh has, and thus I came up with Opera AOI’s central theme.

The musical basis for Opera AOI is techno. I made Japanese-styled pentanic melodies (based on a five-tone scale) within that genre, and then I added the drums and flutes that are used in Noh. The reason why I used techno music here is to create an image of fusing together the present era with the so-different ancient times.

However, while it is influenced by traditional Japanese music, Opera AOI has next to no elements taken from Japanese folk music per se. Japan has many folk songs, and while they’re mostly popular songs that have existed from around 150 years ago, Noh has existed for far longer by virtue of being an entertainment art that was around since the 14th century. And since Noh has received a strong influence from the Buddhist concept of souls going to rest in peace, which are also shown frequently in its plays, it doesn’t really use popular song elements. It’s due to these reasons that I kept on mind the genealogy related to the R&B music from Europe and America more than Japan’s folk music, a good example of it being Jesus Christ Superstar. After all, Jesus~ is also a story about a child of God.

Patrick: For this show, you did everything from composing the music to designing the stage and theatre. What challenges did you face creating it?

Hiroshi Tamawari: Originally, I planned to publish Opera AOI as a radio drama and thus I didn’t make it as a play that could performed live. However, since some people voiced that they wanted to see a visual media version of it, I decided to adapt it to be performed by puppeteers versed in Bunraku: Japan’s traditional type of puppet theater.

My instinct told me it’d be very challenging to express it in this way due to having to combine the synthesized voices with the Bunraku, and since there wasn’t a precedent for it, I was very confused about how I’d start working on it. So well, I began by studying in detail the structure for the Bunraku stage. For a good performance, the puppets need space where moving is easy, which is why a low partition screen is placed at the stage’s forefront. The partition screen hides the puppeteers’ feet and at the same time serves as the ground where the puppets walk, so the acting would feel unnatural if it didn’t exist and the puppets were instead standing on the air.

Additionally, if a puppet has to be operated by three people, the stage needs to be very long and deep for that single puppet to move through it. So there might be three puppets performing on the stage, but there are actually about five people standing over the stage. And aside from the puppeteers, there are also three staff people called the Black Mutes, which take care of setting the stage and operating the props, so the stage would have to account for eight people standing on it. So it was necessary to think in advance about their strings so such a large number of people could move without problems through a small stage.

Bunraku has a lot of restrictions, but on the other hand it allows to use the expression methods characteristic to the puppets, like for example their otherwordly movement or the mechanism that suddenly changes their faces. There are next to no times in which puppeteers aren’t operating their puppets in Bunraku, but for Aoi I place scene in which the puppets aren’t being operated (the scene where Aoi is sleeping). The instant a puppeteer isn’t operating a puppet, that puppet is completely dead; or in other words, they become the puppet itself. So I wondered if it wouldn’t be possible to depict someone that came from the world of the dead by giving a puppeteer control over a dead puppet.

About the stage setting, it can be imagined as similar to a Noh stage. Since Noh plays are acted over a special stage made especially for its kind of theater, they don’t have a large-scale setting. Opera AOI uses a similar disposition as Noh: it has four pillars placed in a square pattern around the stage, and its props are symbolically simple as well. The same goes for the Black Mutes, as I told the staff to keep Noh in mind as we created everything for this project. And that we could actually come up with designs that are clad in the same splendorous atmosphere as the actual Noh costumes is quite impressive too. The true beauty of Noh comes after all from an impressive actor manifesting themselves over an empty space.

Patrick: Opera AOI seems to have a very interesting, ironic message. Midori, the “Digital Diva” vocaloid spirit that inhabits Aoi, is very frightening and manipulative. Nevertheless, the entire show is sung using vocaloid. Is Opera AOI a message in response to the popularity of vocaloid in Japan?

Hiroshi Tamawari: Of course: I really made it in response to Vocaloid’s popularity. Vocaloid was used mainly in video sharing websites, and gradually it became so popular it seemed like wildfire spreading. The dawn of the new era started when videos could be posted as just music with no images, but then people began adding illustrations, turning them into picture stories, then into anime, and within a short time, even adding genuine 3D model CGs to them. And then, they even projected the CGs of the characters into a half-transparent screen to hold a huge concert for their songs. In short, we could say that characters fitting these synthesized voices were established, and then they became wildly popular with them.

I wondered what could be done about a craze that was mainly produced within the internet, and after thinking about it with a cool head, I came up with an objective viewpoint I wanted to depict. Just as you said, such a viewpoint was the “ironic message” in the story. In the world of Opera AOI, the synthesized voices are mere programs, so they don’t exist as actual persons.

However, just one of them was given a method that allows the synthesized voice characters to appear in the real world. Aoi thinks that Midori isn’t just a simple synthesized voice, and instead believes she is an actual person. This allows the Midori lying within Aoi’s deep psyche to control her, which are treated as the symptoms of a mental disorder called the Dissociative Identity Disorder or DID. That’s why she takes on the shape of a realistic Midori, different from the virtual songstress that appeared in that in the real world as an illusion for a show. So the magical image typical of Noh fits perfectly the expression for this kind of story.

Patrick: Are you interested in exploring traditional Japanese music in your future works?

Hiroshi Tamawari: I mainly studied Western music, and it was this basis that I used for musical expression. However, traditional Japanese music uses an entirely different methodology from that of Western music. When I first started working in Opera AOI, I wanted to adopt the expression methods used in Noh music, but in the end it was too difficult and I abandoned the idea.

For example, the flutes used in Noh are arranged purposely to get musical intervals out of order, so they don’t actually follow any musical scales. Also, if the three drums and the flute that form the entirety of the Noh music aren’t played at a specific tempo, the music won’t have a definite rhythm. So a little rhythm break created by a jam session played by four performers is pretty much the backbone of this kind of music. So they play keeping a specific tempo without matching a particular rhythm, pretty much breaking the tempo and rhythm on purpose. Doing this is what gives Noh music its characteristic sense of high tension.

This type of expression is simply not possible in Western, Arabian or Indian music. Even Chinese and Southeast Asian music also have clear concepts of tempo and rhythm, so I think that the shape this kind of music has is something that’s characteristic only to Japan. As a Japanese man, I think I want to assimilate it and allow it to live somehow in the music I make.

Patrick: There is a significant fanbase interested in your works. Have you ever thought about returning to video game music as a freelancer?

Hiroshi Tamawari: I just don’t want to continue writing the same kind of music, i.e. battle music, for a long time. So if I get offers to write music for a game, I’d like to be in charge of the musical approach.

Patrick: Do you think the industry has significantly changed in the many years you have been away?

Hiroshi Tamawari: The style from several years ago in which games take a long time to complete is becoming more and more of a rarity for the products that are currently being made. At the least in Japan, the market has mainly shifted toward games made for smartphones and handhelds, with puzzle games being the most popular among them, making them pretty convenient for killing time. And in these games, neither music or sound effects play important roles. As a first-world country that has a severe problem of declining birthrates and aging population, we have fewer young people that have lots of free time, and that’s why I think that there’s now more games aimed to adults that don’t have much time they can freely spend.

Aside from mobile games, there’s also a lot of MMORPGs being played through the internet, which require a considerable investment of time. However, the core of the fun in them are generally the communities established between fellow players. And even if they are games, the music has next to no importance in the titles in which the main point is moving one’s body around, like in the case for Wii Fit. There are still a few games nowadays that do place emphasis on the music, like rhythm games, but since they don’t have a framework similar to a play’s production, playing them is pretty much playing a game of make-believe that uses famous preexisting songs.

When I think about that situation, I notice I could have never predicted long ago the important point to which the current game music has gotten. As memory constraints are a thing of the past now, it’s possible to play realistic ambient sounds and accompany text lines with full voiceovers. And when a good experience already exists, we shouldn’t add more music to it: making a work overproduced ends up turning it into something stale and cliched.

Thinking about it, I have to say the game music from the previous century — the ones featured in the Dragon Quest, Final Fantasy and Super Mario series — were quite the progressive things due to having been created under so many technological restraints.

Patrick: There are excellent orchestral arranged versions of many RPG classics, but not your works from Vandal Hearts. Would you ever consider arranging your past game works for orchestra?

Hiroshi Tamawari: About orchestrations, I’d like to make them if I ever could have the chance to have an orchestra play my compositions, but since a company [Editor’s Note: Konami] still holds the copyright to my songs, it isn’t something I can just decide on my own. Additionally, I don’t have the musical performance data for these games’ songs at hand anymore, so I think it’d be very difficult to arrange them.

Patrick: Many thanks for your time today. What can fans of your music look forward to in the future? Do you have any messages to readers around the world?

Hiroshi Tamawari: I honestly don’t know in which direction I’ll be heading from now on. However, there are three things I’m always thinking about. The first one is about the relationship between stories and music. This is what was, is, and will always be like my life’s work. I might end up expressing it as an opera, as a game, as a movie or even as a drama. The second is about the possibilities for musical expression that the synthesized voice technologies allow us, as I elaborated on above. The last topic would be about Japan’s traditional music, which I would like to further explore.

As for a message to everyone reading this… I never thought I’d get asked in so much detail about the music I made so long ago, as it’s been over ten years already! And from people overseas besides! I was really surprised to see that people have listened and were interested in my songs for such a long time, so thank you very much for your support!

My most recent work: the VOCALOID Opera AOI movie will be digitally sold to the entirety of the world starting May 21. So if you’re really interested in it, please go ahead and buy it! If we manage to sell enough downloads for it, I’ll be able to make a sequel to Opera AOI. And you can be sure that if I ever get to make a sequel for it, it’ll end up being an even more exciting work! I’ve got all sorts of ideas for it swirling inside my head right now, and who knows, it could even end up being a prequel to Opera AOI’s story.

To learn more about VOCALOID Opera Aoi, check its official site. For an in-depth discussion and celebration of Hiroshi Tamawari’s Vandal Hearts soundtracks, check out Patrick’s latest appearance on videogame music podcast VGMpire.

Posted on May 18, 2015 by Patrick Kulikowski. Last modified on May 20, 2015.