A Study of Michiru Yamane’s “Dracula’s Castle”

Michiru Yamane’s score for the 1997 PlayStation title, Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, is an esteemed accomplishment, one of my favorite videogame soundtracks, and arguably the feature that is mentioned most in comments and articles about the game. Yet practically no literature exists that delves into the soundtrack’s particularities and apparent successes. This is not to assign blame; it’s merely to state that this essay’s intent is to attempt to better critically represent a soundtrack which I believe deserves such representation.

The track that I’ve highlighted for this essay is “Dracula’s Castle.” This is the first environmental track that is heard in the game proper (Note: Symphony of the Night begins with a prologue that recaps the climax of the last game, chronologically speaking, Rondo of Blood), playing in the castle’s entrance once a pervasive darkness lifts and the halls dramatically illuminate. Part of my rationale for choosing “Dracula’s Castle” is that it is one of the more popular tracks. I believe this the case because of its strong establishing associations — its pairing with the new and unusual (for the series) protagonist, Alucard, and the game proper’s beginning — and its strong, driving composition. The other part of my rationale is that the track is defined by a developing “narrative” and clever recursive melodies that help to make it so memorable.

I have put “narrative” in quotation marks because “Dracula’s Castle” has no lyrics, yet it manages to tell a story that effectively evolves in distinct parts. This story is partially a result of the aforementioned recursiveness. Before going on, it is worth clarifying this term. By “recursive” I mean that there is a macro-structure made up of forms that are reused throughout the whole, often for the sake of a general coherent effect. Recursive design can be observed in a variety of media, perhaps most explicitly in architecture: Gothic cathedrals are a good example, with their arched formations that contain more arches within, and their alterations of scale alongside preservations of basic geometric arrangements. Of course, the differences between media mean that exact parallels cannot be made.

“Dracula’s Castle” is recursive by way of having melodic forms and passages that are reused or echoed in some manner. I’ve held back on calling this motivic writing, because I feel that recursiveness describes a much broader and more abstract aesthetic phenomenon that is closer to a kind of formal rhyming. Semantics aside for the moment, I reiterate my belief that this recursiveness strongly assists in the track’s memorability. I also believe that “Dracula’s Castle” has a narrative that serves a dual programmatic purpose: it complements the environment, and it characterizes the narrative arc and protagonist by representing Alucard’s inner struggle and his eventual coming to terms with a sense of purpose.

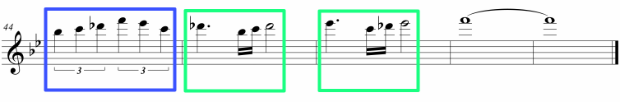

“Dracula’s Castle” is largely defined by two melodic germs. Before going through the piece, I want to highlight these germs. Let’s call them Germ 1 (green) and Germ 2 (blue).

Germ 1 is a four-note melodic fragment appearing around the 22-second mark, in the fourteenth bar. This melody is defined by a briefly lingering note that is followed up by a quick sequence of three notes. It appears throughout much of the track in a way that is consistent with the aforementioned emotional/narrative arc. In its first appearance, the fragment’s fourth and last note, an F#, is actually outside of the established key of G minor. This gives the first prominent melodic moment an edge, or sense of uncertainty. Right after, in the fifteenth bar, the melodic fragment is repeated, but this time the fourth note is C. Between these two instances of the fragment, a tension is created via the strangeness of the F# and the assuredness and “rightness” of the C, even though the dominant tonality remains within G minor. It is a nice encapsulation of the piece’s vacillating drama. It is also worth noting that the intervallic relationship between the F# and C is a tritone, meaning that there is an inherent dissonant contrast between these polarities.  Germ 2 is a sequence of standard triplets, as indicated by the brackets with a “3” , at the 25-seconds mark in the fourteenth bar. Triplets are recognizable for their strong rhythmic quality, and have enjoyed wide use in the music of Japanese videogames, such as combative themes by Kenji Ito and Motoi Sakuraba (to the extent that I feel one can argue for the triplet as a defining regional musical device, when generally compared to the music of, say, American or European videogames). In this first instance, Yamane ends the six-note sequence with a last note in the seventeenth bar. This brings the sequence’s note-count to seven, but there are parts later on in the piece where passages utilize the sequence and lack the last note; so what’s important here is that we have, basically, a sequence of six notes with a particular rhythmic character. Also important is that the rhythmic stressing of the triplets — a kind of bouncy, list-like punctuality — is being used at an emphatic point, where two descents with a justificational tone (almost as a counterpoint to the quickly syllabic curtness of bars 14/15 that carries a hint of dissuasion) are finished off by a brief turn to a brighter key, and thus a brief turn to solidity, or purpose.

Germ 2 is a sequence of standard triplets, as indicated by the brackets with a “3” , at the 25-seconds mark in the fourteenth bar. Triplets are recognizable for their strong rhythmic quality, and have enjoyed wide use in the music of Japanese videogames, such as combative themes by Kenji Ito and Motoi Sakuraba (to the extent that I feel one can argue for the triplet as a defining regional musical device, when generally compared to the music of, say, American or European videogames). In this first instance, Yamane ends the six-note sequence with a last note in the seventeenth bar. This brings the sequence’s note-count to seven, but there are parts later on in the piece where passages utilize the sequence and lack the last note; so what’s important here is that we have, basically, a sequence of six notes with a particular rhythmic character. Also important is that the rhythmic stressing of the triplets — a kind of bouncy, list-like punctuality — is being used at an emphatic point, where two descents with a justificational tone (almost as a counterpoint to the quickly syllabic curtness of bars 14/15 that carries a hint of dissuasion) are finished off by a brief turn to a brighter key, and thus a brief turn to solidity, or purpose.

With these points noted, let’s delve in. Please refer to the sheet music below for bar numbers. The first twelve bars, and all those beyond the forty-eighth, have been excluded because they don’t relate to this article’s emphasis on melodic recursion; however, those sections will be discussed with the belief that they can be understood just as well without illustration. I have also edited the relevant bars to illustrate how I see the two melodic germs reappearing. A quick preview of this should demonstrate how recursive of a piece “Dracula’s Castle” is.

“Dracula’s Castle” begins with a mysterious and vaguely hostile tone. Swirling chords are complemented by simple notes from a bell-like instrument. Eight seconds in, an electric guitar joins the fray as accompaniment, and its abrupt, serrated sound suggests a rude awakening; perhaps, to be allegorical, it is Alucard, disturbed from his slumber. Fourteen seconds in, drums are added, coinciding with the switch to a modal-flavored D chord with a passing G# in the bass. The drums’ thumping rhythm carries a tone of mobilized intent, and the key’s suspension over four bars invokes anticipation; this device will be strategically used at two later points for anticipation and release. Movement is being made towards something dramatic and formidable.

“Dracula’s Castle” begins with a mysterious and vaguely hostile tone. Swirling chords are complemented by simple notes from a bell-like instrument. Eight seconds in, an electric guitar joins the fray as accompaniment, and its abrupt, serrated sound suggests a rude awakening; perhaps, to be allegorical, it is Alucard, disturbed from his slumber. Fourteen seconds in, drums are added, coinciding with the switch to a modal-flavored D chord with a passing G# in the bass. The drums’ thumping rhythm carries a tone of mobilized intent, and the key’s suspension over four bars invokes anticipation; this device will be strategically used at two later points for anticipation and release. Movement is being made towards something dramatic and formidable.

This is followed up by what has already been discussed in the analyses of Germ 1 and Germ 2. The sequence is repeated and ends at bar 21. Bar 22 is the start of a new section, but there is very little that’s structurally different about bars 22-25 when compared to bars 14-21; this can be seen quite clearly on the sheet music. At the risk of being overly simplistic, I think that what is really notable here is the tonal change. Yamane drops the foreign acidity of the F# in the first reformulation of Germ 1, and changes Germ 2’s seventh note to D, rather than G, making the last four notes an unmitigated descent. To me, the section starting at bar 22 represents something more internalized — the tone becomes explanatory and argumentative, as if Alucard has adopted the previous “ideas” as expressed by the music and is critically purveying them under the context of his motivations.

The stressings of this tonal shift are magnified and culminate in bars 26 through 30, nearly all of which reuse Germ 2. Yamane is very clear here about setting up little structures for effect. In bar 26, she has six notes that ultimately form a little rise which she sets right next to a descent in bar 27, whose last two notes are the same. The sense here is that one side of the argument is mounting, and is then countered by a directionally inverted alternative that, although two notes shorter, repeats itself at the end as a sort of rhetorical underline, almost as if to say, “But what about this?” There is then a craggy exchange in bar 28, which makes the most sense retrospectively, but still has its effect in real-time: it’s the struggle before a greater clarity, and ends with a little three-note trill between that pesky F# and E.

I’ve underlined the trill in bars 29 and 30 because I think it’s a case that is more up to personal interpretation as to whether or not it is a reusage of the latter three notes of Germ 1. I’m of the mind that it is not; rather, I think it’s just a rhetorical device that Yamane uses in other tracks at moments of suspension, such as “The Tragic Prince”, also from Symphony of the Night, and “Dissonant Courage”, from Order of Ecclesia. Here is also where the piece’s second prominent suspension occurs. Again, its function is to produce anticipation, but the expectations are more charged, due to the preceding melodic drama and the concurrent urgency of the accompanying strings.

These expectations are met in what is essentially the piece’s build towards a definitive climax. From bars 31 to 38, Yamane makes heavy use of Germ 1. Here, ones senses that some quality of purpose and confidence has been found, even if there is still a flavor of struggle between the exclamations. This switch can be accounted for by two main things, I think. The first is that a lot of the melodic content of the relevant bars is played in an upper octave, which contrasts again the previous material that’s often played in the octave below. Literally and metaphorically, this super-emphasize the voice. The second is that there is a repetitiveness to melodic moments that are already emphatic; for example, note how in the form of Germ 1 in bars 31 and 35 the first and last notes are the same. Not only is there a new confidence: a point is being made of it, too.

The thin vertical lines in bars 33 and 37 may look confusing, but I’ve drawn them simply to show that Yamane is, in addition to reusing Germ 1, also having its instances newly interrelate. Here, the quick trios of notes act on their own and have their last note serve as the starting part for another divisible instance of Germ 1; e.g., the second-to-last note in bar 33 is followed up by a trio, even while it itself is at the end of another trio. This makes the most sense when listening, and I encourage doing so here more than ever (starting at 51 seconds and going until a minute-and-five-seconds) to get the best sense of what I mean.

From bars 39 to 44, Germ 2 is used in a progressively dramatic manner. Generally, it has the same basic function as it did in bars 26 to 29, where its indenting rhythmic quality and close proximity of notes call attention to its rises and falls, and give it an exceptionally accentuated voicing, but now it can be divided into three distinct parts (thanks largely to bars 40 and 42 having only one note in the lead melody, which create noticeable spans of separation): an initial appearance, a second appearance that is formationally similar and higher on the scale, and a third appearance that is even higher on the scale, melodically continuous for two bars, and in a different key. The sense here is not so much of opposing points of view, but of a singular, determined straining. This leads right into the last instances of a germ, with Germ 1 continuing the present theme of ascension and also holding onto that aforementioned (bars 31 – 38) repetitiveness: again, the first and last notes of each instance of the germ are the same. These are, without question, the most emphatic moments of the composition; and it’s entirely relevant, as the piece proceeds to its climax in bar 47. A triumphant F note, seemingly expressive of a full emergence into “light,” is held for two bars. This is the final significant suspension, and it acts as an exhalation.

What is interesting here — at a minute and twenty-four seconds in (beginning where this article’s illustrations end) — is that Yamane does not dwell on victory. Instead, she pushes us beyond the luminous emergence into a mysterious, twinkling, blustery upper atmosphere. Personally, I can’t help but be reminded of the castle entrance’s purplish sky, occasionally torn by lightning. This is a nice twist that complicates the decisiveness of this condensed version of Alucard’s arc, which also ends uncertainly in the actual narrative, despite his victory. It also echoes the piece’s preamble prior to the loop (restarting on the fourteenth bar): again, we have the windy soundscape with “bells,” the appearance of an electric guitar, and the escalating percussion.

I’ve limited the reach of this essay for readability and because I think its emphases are, relative to “Dracula’s Castle” and given the options, the most interesting to talk about. I also think it’s important to acknowledge that although the observances I’ve made here have helped to develop my appreciation of the piece — hopefully, it does the same for others (or inspires fresh approaches to other music that employ ideas on instrumentally embedded narrative or recursiveness) — the deepest enjoyment of music is ultimately, and uniquely, unexplainable. This is, happily, part of the pleasure of our relationship with the art.

Special thanks to Michelle Ball for providing the sheet music.

Posted on October 19, 2014 by Ario Barzan. Last modified on October 20, 2014.