Koichi Namiki Interview: From the S.S.T. Band to Blind Spot

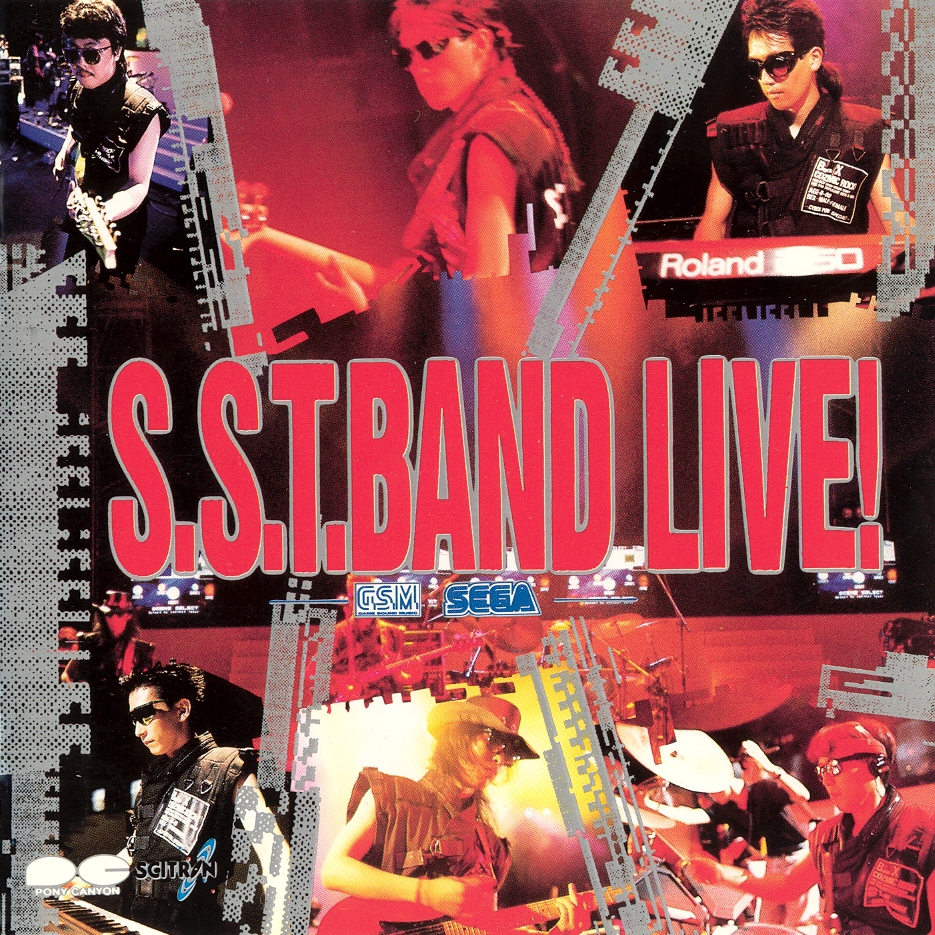

Koichi Namiki worked at Sega during the late 80s, writing music for arcade classics such as Galaxy Force, Thunder Blade, and Super Hang-On. The longest-standing member of Sega’s in-house rock band, the S.S.T. Band, he brought game music to the masses with studio and live renditions of arcade favourites. Since leaving Sega, he has scored diverse games and is a prolific vocal arranger.

This interview is adapted from The BEEP Book: Documenting the History of Game Sound. This 860-page book, authored by interactive audio academic Karen Collins with contributions from VGMO editor-in-chief Chris Greening, features transcripts of interviews with over 100 game audio professionals from a range of areas of game sound’s history. The book can be downloaded from Amazon and a two-part physical version was also sent to Kickstarter backers.

Interview Credits

Interview Subject: Koichi Namiki

Interviewer: Karen Collins, Chris Greening

Editor: Chris Greening, Karen Collins

Translation & Localisation: Alwyn Spies, Emil R. Nilsson

Coordination: Chris Greening, Karen Collins

Interview Content

BEEP: It would be interesting to learn about your musical background. Did you have any particular inspirations for your early game scores?

Koichi Namiki: In the beginning, it was pop music. ABBA, for instance, and the Beatles. They made me interested in music and led me to realize that I also wanted to play something. But I wasn’t good at singing, so I started playing the guitar. And then I wanted to start a band and play music, but it didn’t matter how much I searched, I couldn’t find a vocalist that I liked. So I started thinking that the only way was to do it without a vocalist.

And right at that time, Fusion and Crossover were really popular in Japan. So I started listening to that kind of music and there was a Japanese band called Casiopea, which I imitated – I did covers on their songs. And later on, Casiopea’s guitarist Issei Noro became the producer of S.S.T Band.

BEEP: Can you tell us about how composed game music back in the 80s. You started with Super Hang-On?

Koichi Namiki: First, let’s talk about the process of composing music. The composing staff at Sega were, by coincidence, people that played in bands – there were a lot of people with band experience. People with band experience have a way of making music so that it can be performed on stage. Because of that, the music we created wasn’t so much so-called game music, but rather music that a human being could perform. It wasn’t that this was what we aimed for. That was the only thing we could do.

Using Super Hang-On, at the time, I could only play the guitar. So I wrote all the music while playing the guitar. Using the guitar solo for example, I listened carefully to music recorded on a tape and then I wrote the score down. So I used recordings that sounded like a real guitar performances. Some years after, I was actually asked by Wavemaster [editor’s note: Sega’s in-house music division and record label] to arrange music for the 20-year-anniversary CD of Super Hang-On and play the songs and the guitar solos that I had put into the game on my own guitar.

BEEP: How much freedom did you have to write music for games in the early days?

Koichi Namiki: We had about 60% freedom. The game designer is a pro at creating the idea for the concept of the game. He’s not a pro when it comes to music, so he left that task to us. There are designers who are really particular, but usually the music making is left to us.

BEEP: Is that still the case today as well?

Koichi Namiki: Yes, that is usually the case now as well. In the world of games especially, the designer isn’t a professional composer, so it’s different from when a usual artistic director makes things. There aren’t many people who are really particular – even if they want to say something about the minor details, they don’t know what to say. They don’t know how to say what they want to say. Sometimes there are game designers who give you a sample and ask you to use that as the image when you create the music. But usually you only have a PDF file with the concept.

The production process has changed quite a bit, however. In the past, the only recordings were with MTR. So we recorded a piece and transcribed it into written music. Now it’s not like that at all any more as there’s a thing called DAW (Digital Audio Workstation). Now you can use that to make music, so the performance and the composing and the arrangement – everything, even when it’s time for the mixing – it’s all a simultaneous process.

BEEP: You were the guitarist for the S.S.T. Band, which performed live and studio renditions of Sega classics from 1988 to 1993. What made you decide to take your music and start distributing it and playing it outside of the games?

Koichi Namiki: The first incentive came in 1986. There is a building in Ikebukuro called Sunshine City and in that building there is a space called Fountain Plaza, which can be seen both from below and from above. There was an event for After Burner and, at that event, staff-only bands could perform. In the beginning, the performances were centred on the music of After Burner. And that was how it began. Then that became popular and we were asked to continue playing.

So the company gathered band members. There were only two of us that continued to participate from Sega itself (editor’s note: Koichi Namiki and Hiroshi Kawaguchi). On the sixth anniversary of the release of the Master System, there were events in Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka. These events were really appreciated by the customers and we received encouraging critique. So we thought it was a shame to let it end just like that.

BEEP: How did your band go from writing game music to performing live? Were everyone at Sega experienced performers?

Koichi Namiki: Basically, all those involved were people who were actively or previously involved in bands. For example, I had played the acoustic guitar from the age of 14 and later moved on to the electric. That said, for many of us, we performed music in our homes – they couldn’t perform it on stage, but they were good at making music. There were two kinds of people: those who only made music without performing, and the people who already played in bands and gave concerts.

BEEP: S.S.T. Band went on to release several arranged and original albums. How did you transition from doing live performances to making studio recordings?

Koichi Namiki: At Sega, we had made LP recordings of game music for some time and shifted into CDs. At first, only the sounds of the circuit board were available to consumers. However, the record company (editor’s note: Pony Canyon) asked us what we thought about releasing albums as a band. So we learned how to arrange and perform music with CDs in mind. Through this, the S.S.T. Band gradually took shape.

So it happened in a natural way. I don’t really know much about how things were at other companies, but I believe that similar albums started to be produced at almost the same time by other companies, right? So, I think that was a thing that took place in the entire industry.

BEEP: On that note, S.S.T. Band were the first video game band of its time and inspired many imitations: Konami’s Kukeiha Club, Taito’s Zuntata, Capcom’s Alph Lyla, and Data East’s Gamadelic to name a few. How did these bands interact? Was there much rivalry?

Koichi Namiki: Actually, at the end of the 90s, there was the annual Game Music Festival series where game music bands and soloists performed. At one festival, Mr. Motoaki Furukawa [of Konami’s Kukeiha Club] was standing on the same stage as I. After the concert was finished, we went out drinking and became friends. As a result, I got to know a lot of people that performed at the time. For example, Alph Lyla, Gamadelic, Cho Aniki, etc. I became friends with all of them. And we’re still friends.

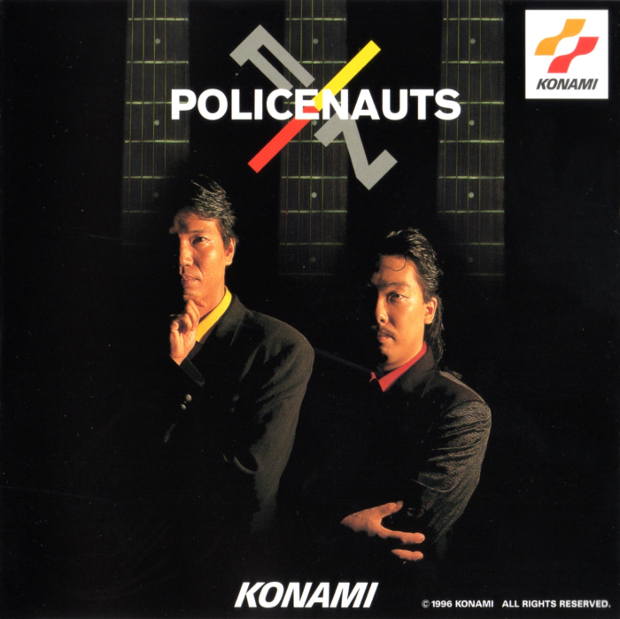

BEEP: You cemented this relationship by recording Policenauts F/N with Motoaki Furukawa. What led to this collaboration of Sega and Konami veterans?

Koichi Namiki: When I became a freelancer, a friend of the bass player in S.S.T. Band worked for Konami and I came in contact with him and I worked on a tour with Konami. Therefore, I became friends with a lot of people that worked for Konami. Amongst those people, there was this one director and he wanted me to make an album with Mr. Furukawa, Policenauts F/N.

We were asked to make five songs each. It was basically just the two of us [that worked on that album]. Well, there was a chorus, but except for that, it was just the two of us, the engineer and the director. We were in the studio just the four of us. And under those conditions, we did the recording. It was really stimulating.

BEEP: Talking more generally, how do you approach arranging music from games for the purpose of album releases?

Koichi Namiki: That is a difficult question. In most cases, I wasn’t really thinking about anything complicated. For the 20th anniversary arranged CD for Galaxy Force and Thunder Blade, I challenged myself. The team didn’t use MIDI at any point. Instead I played everything. We only used a drum loop, and to that I played the bass and all the guitar parts. We also added all the chords one sound at the time. So I played the guitar on some forty tracks and we didn’t use a synthesizer at all. Even though I could have used a synthesizer, it wouldn’t compare to the sounds of a professional player, so I thought it was cooler to play the instruments myself. It was a lot of fun to do!

BEEP: You are presently a member of Blind Spot, considered a spiritual successor of the S.S.T. Band. What inspired you to form this band?

Koichi Namiki: Because of [certain] conditions at Sega, S.S.T Band was dissolved. But even after that I was active as a member of B-univ with Takenobu Mitsuyoshi. Then one day, I left Sega to become a freelancer. After all, you have to create jobs yourself, they don’t just come to you.

Four years ago, the Tohoku earthquake happened. At that time, I looked at the broadcasting on the TV and it really brought me down. I started to wonder if there was any kind of project that could make everybody happy again. If the fans said that they wanted it, then I have to do it, right? I have to try my best! That’s how I came up with the idea for reviving the S.S.T. Band. Simply put, it didn’t work… At the time, Sega had an official band called [H.], and we could no longer be the official band. So it wasn’t that easy.

BEEP: So you changed the name?

Koichi Namiki: Yes, we changed the name of the band from S.S.T. Band to Blind Spot. Blind Spot was actually the title of an original album that we had composed ourselves – the music wasn’t inserted into any game. So, the band Blind Spot was born and we have been active for two or three years, giving concerts two or three times every year and we have released a CD and a DVD.

When I looked at people’s faces at the first concert, they were all crying. Really crying; real tears! Everybody had made placards saying that they had been waiting for us to come back. People were really happy, so I thought we have to continue. Not business, you know, but live performances! I felt that we should continue with this as long as we can.

BEEP: What’s in store in the future?

Koichi Namiki: I want to continue with Blind Spot, so I would like to, if possible, travel around the world. So please keep in contact!

Readers can follow the latest activities of Blind Spot at their Facebook page. For more interviews like this, purchase the The BEEP Book: Documenting the History of Game Sound.

Posted on January 6, 2017 by Chris Greening. Last modified on January 15, 2017.